If you try to imagine your way back into the early 20th century streets and laneways of The Ward — the dense immigrant enclave razed to make way for Toronto’s City Hall — you might pick up the sounds of newsies and peddlers hawking their wares, the clanging of the area’s junk and lumber yards, and shrieking children playing on the Elizabeth Street playground north of Dundas.

Those streets would also reverberate day and night with a jumble of languages — Italian, Yiddish, Chinese. The dialects and accents of these newcomers were considered to be not only “foreign,” but also proof (to the keepers of Toronto’s Anglo-Saxon morality) of the area’s worrisome social and physical failings.

But despite the fact that many mainstream Torontonians saw The Ward as an impoverished blight on the face of the city, the neighbourhood resonated with energy and culture and music — evidence of the resilience of the stigmatized newcomers who settled there in waves from the late 19th century onward.

Photographers recorded fiddle players and organ grinders with their hurdy gurdies, playing as mesmerized children listened. After their shifts ended, one 1914 account noted, labourers whiled away their free times playing mandolins or concertinas as they sang rags and the Neapolitan songs so popular at the time.

“When sleep in crowded rooms seems all but impossible,” journalist Emily Weaver observed in The Globe and Mail in 1910, “the people of ‘The Ward’ are astir till all hours, and the Italians amuse themselves by singing in their rich sweet voices the songs of their far-away homelands or dancing their native dances to the music of a mandolin or guitar in the open roadway beneath the stars.”

Some residents brought music into their homes. In a 1955 memoir about growing up in The Ward in the 1910s, Marjorie Johnston recalled the day her father brought home a new gramophone and three records – all British dance hall standards. Years later, she wrote, “I have a nostalgic memory of a cozy little parlour with fashionable red paper on the wall, a hanging lamp of ruby glass, and a little girl on her father’s knee listening to that record pouring forth from the brass horn.”

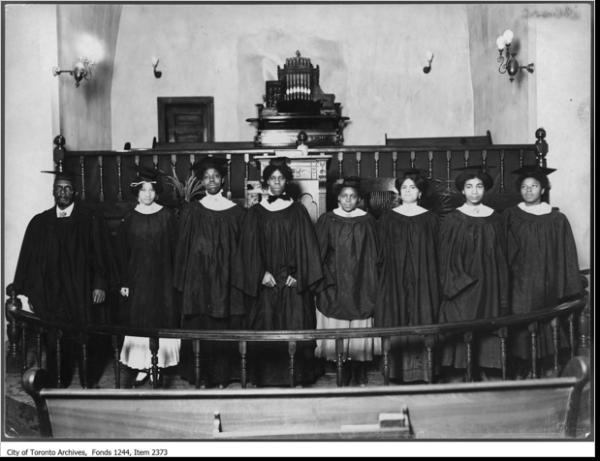

The Ward’s sound was sacred as well as profane. Celebratory music could be heard at weddings, bar mitzvahs, baptisms, and confirmations. On days of worship, the area’s synagogues and black churches (the Agnes Street Bapist and the British Methodist Episcopal) resonated with liturgical music – gospels, hymns, cantorial songs: a medley performed in religious buildings located scarcely metres apart.

In a telling example of The Ward’s social dynamism, several Jewish businessmen in 1909 bought the black church at the north-east corner of Dundas and Bay and turned it into the Lyric Theatre, which performed Yiddish plays and concerts. (After the Lyric let out, the theatre-goers would head over to Altman’s, a Yiddish bakery at Elizabeth and Louisa, for a late-night snack; the City Hall parking permit office is located at that spot today.)

Music could also be heard in factories. Joseph Shlisky, a young Polish Jew forcibly brought to Toronto to perform in a cantorial choir, was singing at his sewing machine in the Eaton’s factory one day when Lady Eaton overheard him. Enchanted, she offered to pay for his musical education. Shlisky later made his way to New York, where he went on to be one of the great cantors of his generation (A socialist choir of Eaton’s factory workers formed to perform Yiddish folk songs with political inflections).

Meanwhile, at Central Neighbourhood House, an immigrant settlement agency on Gerard St. near Bay, the staff in 1915 set up a community music school for children as a means of improving their civic education and social development. The school produced concerts featuring the sort of Western classical music considered, at the time, to be crucial to the Canadianization of foreign-born children.

By the 1920s, the Chinese residents who had settled in The Ward began to establish community organizations, such as Gee Tung Tong Club and the Ship Toy Yuen Dramatic Society, specifically to perform highly ritualized Cantonese operas in halls on Elizabeth and Dundas streets.

Besides these informal street-level sounds, The Ward was ringed by major commercial performance venues (e.g., Massey Hall, Shea’s Hippodrome, the Pantages and Victory theatres, etc.) that played a critical role in connecting Torontonians to international musical trends, everything from dance hall and vaudeville to opera and Klezmer. The performers walking those boards were locals, too. One Chinese dramatic society rented the burlesque theatre at Queen and Bay for operas on Sundays, when the strip tease dancers weren’t peeling.

Come the 1940s and 1950s, the locus of performed music in The Ward shifted north to the cafes and clubs of the Gerrard Street Village, where young people congregated at intimate venues featuring the folk and jazz musicians who later came to be associated with the Yorkville hippie scene.

This sustained urban symphony eventually drew to a close as municipal officials in the post-war period began expropriating and redeveloping The Ward to make way for hospitals, offices, and Toronto’s new city hall.

By that point, the area’s dominant sounds emanated from that quintessential instrument of post-war progress: the bulldozer.

“The Ward: The Songs and Sounds of a Lost Toronto Neighbourhood” will be performed at Lula Lounge on April 26. Co-presented by ERA Architects, The Metcalf Foundation, Coach House Books and Spacing, the show will feature a band led by David Buchbinder, Michael Occhipinti and Andrew Craig, playing music linked to The Ward and the period when it was Toronto’s most visible immigrant neighbourhood.

The line-up includes selections from a sheath of klezmer sheet music given to Buchbinder by Stella Barsh 20 years ago. Barsh’s grandfather had a band that performed in Toronto a century ago. Many were standards, but a good number of them seem to be original songs written and perhaps played in that lost neighbourhood. Stella Barsh attended the first workshop of the show at Soulpepper last spring.

The tickets are $20, and available at the Spacing Store (401 Richmond St. W.) or on EventBrite.

One comment

What’s the name of the Marjorie Johnston memoir?