When the flood water on the Toronto Island eventually recedes it will reveal a damaged and possibly forever altered landscape.

For the first time in recent memory, a large portion of the Island is underwater and largely inaccessible to the thousands of people who normally visit in early Summer.

Homes are surrounded by sandbags and the Rectory Cafe has already permanently closed due to a lack of customers. So far, the damage is estimated to be around $4.88 million (most of that in lost ferry revenue,) but that figure could climb if the Island park remains closed through to the end of August.

However, there wouldn’t be an Island park at all if it wasn’t for the vision of two of Toronto’s most prominent leaders in the 1950s.

Of course, the Island was a destination long before the post-war era. Before the arrival of Europeans, the Mississaugas used the area, which was originally a lengthy sandbar bisected by pools and streams and connected to a marsh at the mouth of the Don River.

Elizabeth Simcoe, the wife of Toronto-founder John Graves Simcoe, wrote about a visit to the Island in her diary in 1790s and in the decades that followed, hotels opened on the Island with the first ferry services delivering guests from the mainland.

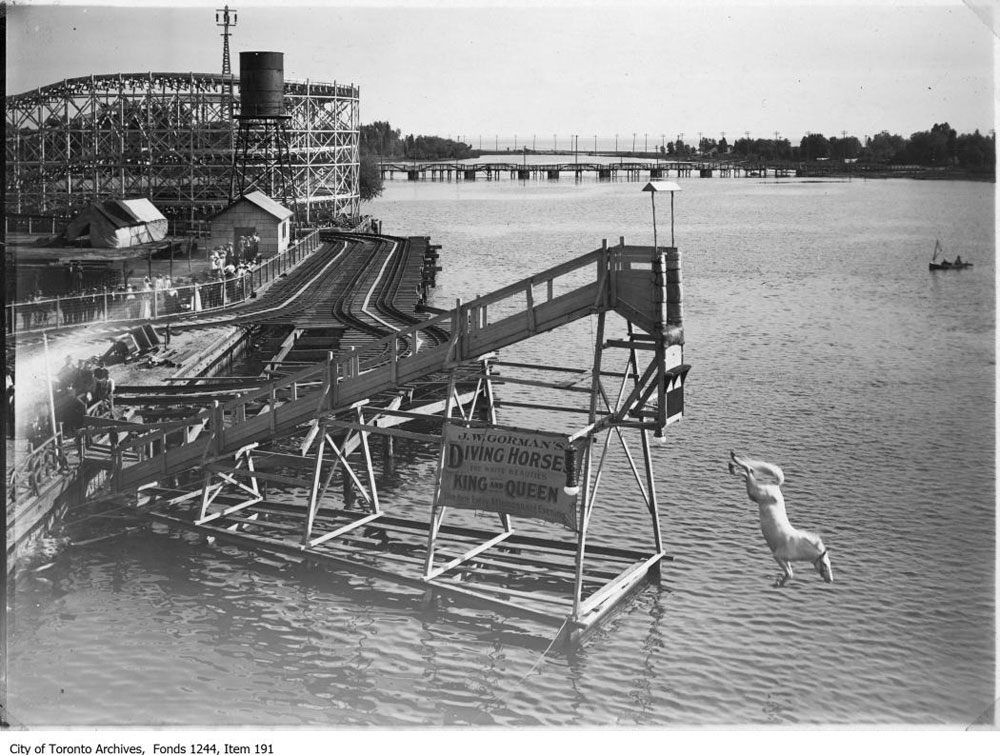

In time, Hanlan’s Point became a Toronto version of Coney Island in the early decades of the 20th century, with a baseball stadium (where Babe Ruth hit his first professional home run), a wooden rollercoaster, and all manner of fairground attractions.

In 1931, 2.2 million people visited the Island by ferry. A record 100,000 people crossed the harbour in a single day that year (the recent one-day ridership record is 32,000), but the end was rapidly approaching.

The amusements at Hanlan’s were demolished to make way for the Island Airport in the 1937 and by the Second World War, the Island had become largely residential, with a mix of summer homes and year-round dwellings.

The Island as we know it today is the result of a decision to make the land the property of the new Metropolitan Toronto government under chairman Frederick G. Gardiner and parks commissioner Tommy Thompson in 1956.

For Thompson and Gardiner, the Island was a key part in their plan to modernize Toronto.

By combining the power of the 13 cities, towns, townships, and villages that fell under Metropolitan Toronto umbrella, there would be new subways (three lines in a little over 15 years), new expressways on the waterfront, up the Don Valley, and down Spadina, new sewage plants and other key infrastructure, and miles of new parkland for the growing city to enjoy.

There had been a various plans to develop the Islands since the closure of the amusements at Hanlan’s Point. In 1947, the Toronto Planning Board proposed connecting the Island to the mainland by road and adding parking, shopping, and hotels.

In 1951, the Toronto Planning Board and the Toronto Harbour Commission unveiled a joint plan to build a new amusement park, regatta course, and neighbourhood of apartments accessible by a road tunnel under the Island airport.

Tommy Thompson’s vision for the Toronto Island Park was no less drastic than those pitched and trashed in the years before, but with the backing of Metropolitan Toronto, Thompson had the political clout to make his vision a reality.

In 1958, his Parks and Recreation Committee hired urban planner Macklin Hancock and his firm Project Planning Associates Ltd. to produce a master plan for the Toronto Island Park.

Project Planning prepared the blueprints for Don Mills and Thorncliffe Park suburban developments in Toronto in the 1950s and their concept for the Island was centred around a new pedestrian promenade on Centre Island.

Most notably, and controversially, Metropolitan Toronto planned to make the necessary space by completely clearing the Island of all residential properties by the end of the 1960s.

The leases on most of the offshore residential properties were to be terminated as they came up for renewal and the land razed. The Island main street, Manitou Road, which contained a movie theatre, restaurants, a boat rental business, and many of the Island’s entertainment offerings was to be similarly demolished.

Metro Toronto approved the plan in February 1956 and began clearing, raising, and landscaping the Island soil more or less immediately. The goal was a “a fresh holiday like experience” for everyone who visited, with ample room for picnicking, swimming, or sunbathing.

It was to be a summer playground away from downtown, accessed by improved ferry service, or maybe a chair lift like the one over the one just built over Rhine in Cologne, Germany.

“The Island atmosphere should be water oriented,” a March 1963 report explained. “It should be a day of masts, boats, boat rides, pennants, swimming, sand, gay umbrellas, feeding ducks, crossing bridges, a stroll on the pier, a band on a showboat, a meal overlooking the water, and to finish, a ride on a roller coaster with a water splash. In short, it should be fun!”

In other words,”entertainment without hurdy-gurdy.”

Among the first new structures built on the Toronto Island were a set of picnic pavilions and concession stands designed by architects Venchiarutti & Venchiarutti.

Prior to being hired to work on the Island, Venchiarutti & Venchiarutti designed Colony Plaza, the strip mall at Lawrence and Warden Avenues where Tim Horton first gave his name to a donut shop.

The firm almost wasn’t hired at all. At the time, Tommy Thompson was under pressure to adopt shelter designs City of Toronto parks commissioner George Bell had borrowed from Florida and used in High Park.

“In a loud voice, Mr. Thompson said he didn’t see why he should have to follow Mr. Bell in everything that Mr. Bell does for parks,” reported The Globe and Mail. “The very idea makes him boil.”

“Toronto Island should be developed in a typical Toronto style, not something copied from Buffalo or any other U.S. centre, Thompson said.”

Four Venchiarutti & Venchiarutti structures of varying sizes were built near the Centre Island ferry dock. These were distinguished by their glazed brick walls and zig-zag, reinforced-concrete roofs that were meant to “reflect the open land and water characteristics of the Toronto Islands.”

The largest of the set, which included washrooms, was located beside the Centre Island ferry dock. A picnic pavilion with a fireplace was located a short walk away on the edge of Long Pond and a concession stand was situated along the Avenue of the Islands.

A second concession stand, which has now been demolished, was located on the current site of Centreville.

In revealing the designs to the public, Metro parks claimed the Venchiarutti & Venchiarutti structures were “almost hooligan proof.”

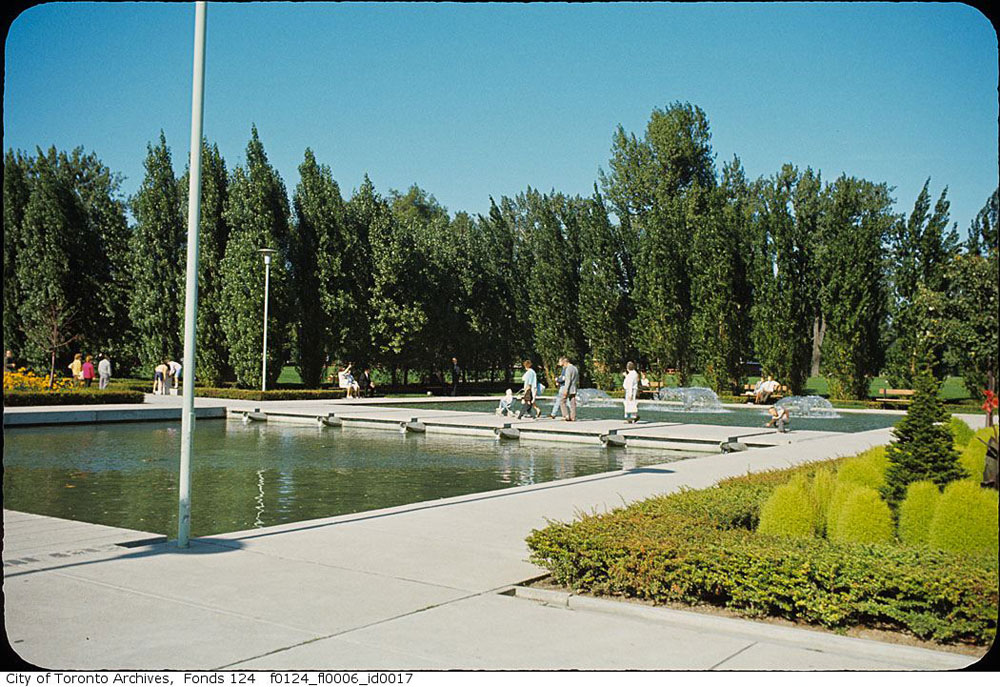

Around the same time, historic Manitou Road was demolished to make way for a landscaped walk with little pools and floral planters designed by Hancock, Little, Calvert Associates, the architecture firm associated with Macklin Hancock’s Project Planning Associates.

Near the Manitou Road bridge, Hancock, Little, Calvert Associates also designed a hexagonal restaurant with a deeply folded roof like a paper fortune teller. Originally known as the Iroquois Restaurant, the $70,000 building was controversial because Thompson planned to use it for a “high-class” restaurant—a steakhouse, maybe.

Fred Gardiner thought a fancy restaurant would be at odds with the Island Park concept. “The picnic-type class who would patronize it would not want Royal York-type menus,” he said, suggesting the restaurant serve the “hamburger and hot dog trade” instead.

In the end, Thompson and Gardiner compromised by building the kitchen, storage, and patio first, leaving the decision on theme for later.

Also as part of the landscaped walk, two bathing stations were also built on the Lake Ontario side of Centre Island and a Y-shaped pier that projected out into Lake Ontario.

The site of the pier was originally supposed to be the location of a 2,400-capacity amphitheatre, but this and many other planned features of the Toronto Island Park were dropped or heavily altered.

The plans for an amusement park on Centre Island changed the most. Now known as Centreville, it was supposed to consist of a model town called Cosmorama, “contain[ing] world famous landmarks laid out in a new, integrated town plan.”

Metro Toronto hoped countries and cities around the world would donate scale models of famous landmarks to the miniature town.

There was also supposed to be a “Sportsland”, with tennis, deck tennis, miniature golf, clock golf, quoits, handball, archery, and horseshoes, and a “Funland,” a place for “youthful good times,” closer to the east end of the Island.

“[Funland] will consist largely of mechanical rides of the roller coaster, ferris wheel type, but no games of chance will be permitted,” a Metro Toronto 1964 report explained.

“A collection of merry-go-rounds and dodgem cars will be integrated together with a waxworks display and other permanent type exhibits: (e.g., a display of antique automobiles.)”

Four additional picnic shelters that were designed by noted Modern architect Irving Grossman were added to the park in 1962. His shelters looked like clustered parasols and were primarily located along the footpath from the on Hanlan’s Point ferry dock.

By the mid-1960s, however, Metro Toronto’s plans for the Island were beginning to run out of steam. While some Island tenants left with relatively little fuss, others dug in deep, beginning a protracted battle to remain on the Island that wouldn’t be resolved for decades.

By 1963, about 370 homes remained on the Island, most of them east of the Avenue of the Islands. Approximately 100 more were removed by the time the demolitions were halted for good.

Today, 262 residential properties remain on Ward’s Island and Algonquin Island.

Meanwhile, Tommy Thompson’s Island Park remains mostly unchanged from the 1960s.

2 comments

I want to live on the Toronto Islands!!

That’s why I support converting the Island Airport into a car-free residential community of 100,000 people. That way everyone who wants to live in a car-free community can do so.

Imagine my children being able to play freely and not be terrorized off the street by car drivers. Imagine my children being able to get on their bicycles and be in the Island park in 10 minutes.

Imagine a car-free neighbourhood with everything within a 10 minute bike ride. Shops, bank, church, grocery store, cafes, etc, etc. Nothing more than 10 minutes by bicycle on car-free streets.

Fantastic article uncovering an important but forgotten component of our civic history.

Kudos Chris Batemen!