“The watching Torontonians didn’t cheer, didn’t wave,” reported the Toronto Daily Star on August 5, 1967, as “Caribana” left Varsity Stadium on Bloor Street for a mile-long procession. “West Indians said carnival time in their sunny island homes was never so quiet.”

The event, which was the Caribbean community’s gift to Centennial year celebrations, began with the Carnival and was capped with festivities on Centre Island, a Sunday market and cricket match, a youth fashion show, and boat cruises.

One week later, newspapers reported that more than 50,000 people had attended Caribana. At that time, the Caribbean community numbered around 10,000 people, but both Mayor William Dennison (1967–1972) and Parks Commissioner Tommy Thompson made public statements hailing the event.

“I hope there are many more Caribanas on the island in years to come,” Thompson said to the Star, before donning a Caribbean-style straw hat and performing a solo dance before a cheering crowd.

In more recent years, Carnival has been marred by inflammatory headlines: “One dead, two wounded in parade route shooting,” CP24 reported about an incident that took place after the grand parade was over.

Post-grand parade parties have also been marred by anti-Black racism, such as in 2018, when the City of Vaughan abruptly cancelled a Carnival event just hours before doors opened, citing overcrowding and noise — complaints that are often levelled against other Black festival such as Afrofest, but not the numerous other “white” festivals that take place across the GTA in a typical summer.

Obviously, 2020 is different. For the first time in 52 years, Carnival celebrations were cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. While Toronto Caribbean Carnival organizers held a “Virtual Road” event on August 1 — a 13-hour live Zoom stream featuring multiple DJs from different countries — many still felt an emotional loss of not “going on de road” in the spirit of Carnival.

Additionally, organizers estimate that by cancelling Toronto Carnival, approximately $400 million to Canada’s GDP was lost, the bulk of that coming from tourism, transportation, food, and beverage services. Then there are the promoters, who bank on sold-out boat cruises, parties, and live entertainment.

Right now, however, the very thought of hundreds of thousands of Black people taking up public space would be political.

“White people are more afraid of Carnival than coronavirus,” writes Radheyan Simonpillai in Now Magazine’s Carnival 2020 issue. “They’re more willing to crowd Trinity Bellwoods Park during a pandemic than join the crowds at Lake Shore Boulevard during the colourful festivities celebrating Caribbean culture. They’re eager to escape to the cottage to get away from the city during Carnival weekend.”

COVID-19 has forced us to rethink so many aspects of our society, and Carnival is no exception. Organizers are in a wait-and-see mode for next year’s events. Yet what if Carnival 2021 wasn’t just about economic gains for the city or parties and boat cruises, but was reimagined as an extravaganza that had, as one aim, the funding of Black excellence?

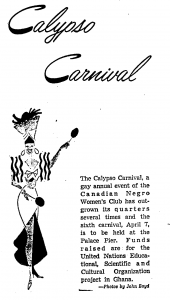

This might sound like a revolutionary idea, but before there was Caribana, the Canadian Negro Women’s Association (CANEWA) organized a Calypso Carnival that had as its main purpose fundraising for Black community, at home and abroad.

Following immigration reforms in 1962, when Parliament revoked overt racial discrimination from formal policy, and then the introduction in 1967 of the “points system,” which placed an emphasis on education and professional skills, immigration has fundamentally changed the demographics of Canada.

However, these changes also created a form of cultural amnesia to the histories and contributions of Black Canadians prior the 1960s. Not all Black people in Toronto at that time had immigrated from the Caribbean. There were African Canadians who had left Nova Scotia, rural Ontario, and elsewhere to reside in the city.

Kay Livingstone (1919–1975) was one of those people. Born in London, Ontario, she was one of eight children of James and Christina Jenkins, co-founders of The Dawn of Tomorrow, one of the longest in-circulation Black Canadian newspapers. After moving to Toronto, in 1951, Livingstone helped to establish the Canadian Negro Women’s Club (later, CANEWA), serving as president until 1953. While at first the club was called “The Dilettantes,” and mostly organized tea and garden parties, Livingstone advocated changing the name and mandate to “become aware of, to appreciate, and further the merits” of Black Canadians.

From 1956 to 1964, CANEWA’s Calypso Carnival celebrated Caribbean culture and functioned principally as a fundraiser for Black initiatives. As writer Lawrence Hill recalled in his 1996 book about CANEWA, “Few adults in Toronto could name the Black community group that, for a quarter of this century, set up student scholarships, levelled vigorous protests against media and police authorities, initiated the celebration of Black history in Ontario, organized the precursor to Caribana and raised thousands of dollars for community projects.”

On April 23, 1962, The Globe and Mail reported that “Kyla Lynn Dey, 2, gets her first taste of ackee from Mrs. Edward Green. Eugenie Oliver, right, breaks a West Indian patty, a native dish of pastry, meat and spices, one of the many to be served at the Calypso Carnival to be held at the Palace Pier [on] April 27. The proceeds of the party, sponsored by the Canadian Negro Women’s Club, will be used to aid work in Ghana.”

The Palace Pier, created in 1927 by a provincial agency, was a year-round amusement similar to Sunnyside Beach (which opened in 1921). By the 1950s, the Palace Pier thrived as a dance and banquet hall until it was destroyed by fire in 1963.

CANEWA’s Calypso Carnival celebrated food from the Caribbean, and some years, it held an African dance and art show at Casa Loma. The event introduced Toronto’s very white population to limbo dancing and calypso music. In some ways, it helped to create the socio-cultural conditions that would allow a Carnival on the scale of Caribana to exist.

As an organization, CANEWA was quite small, never reaching more than 40 members. But it has left us with an example of what is possible. What if Toronto Caribbean Carnival organizers created a scholarship fund that went directly to aiding Black community? Some of the proceeds could, for instance, go toward establishing Eglinton West’s Little Jamaica, a section of town replete with Caribbean history and culture that has been threatened with erasure due to the Eglinton Crosstown, as a Caribbean heritage zone, like Greektown, Little Italy, or Chinatown?

When the 1.2 million attendees eventually return to the lakeshore to “play mas” and “go on de road,” we will have a unique opportunity to not only make demands of government to address the anti-Black racism that has marred Carnival, but also to empower revelers, masqueraders, and onlookers to party with a new sense of purpose.

Cheryl Thompson is an Assistant Professor in the School of Creative Industries at Ryerson University. Her next book, Uncle: Race, Nostalgia and the Politics of Loyalty will be published by Coach House Books next February. Cheryl will be discussing Emancipation Day online today (Aug. 5) at 4 p.m. at ROM Connects (tickets here). Follow her on twitter at @DrCherylT.

Photos courtesy (from top) Caribana 1971, by Jeff Goode and the Toronto Star; The Globe and Mail, March 23, 1961; the Toronto Star, November 5, 1955