Toronto, arguably, is in the midst of what the city may look back on as a golden age of landscape architecture and design. In the past 15 years, Waterfront Toronto has made increasingly bold investments in landscape and public realm, from discrete interventions, such as Wave Deck Park and Sugar Beach, to more ambitious parks (Sherbourne Common) and then highly ambitious landscaping mega-projects worth almost $2 billion — namely Corktown Common and the naturalization of the Lower Don Lands. The latter two, I’d predict, will be as profoundly transformative to Toronto’s eastern waterfront precinct as Central Park was to Manhattan.

These projects come alongside other stellar landscape architecture undertakings — the Grange Park revitalization (2017), The Bentway (2018), the West Toronto Railpath (2009) and, of course, the Evergreen Brickworks (1991). The leading lights of the profession — Claude Cormier, Michael van Valkenburgh, Janet Rosenberg, Marc Ryan — work or want to work here because so many of these commissions come with layered and complex mandates, not just recreational aesthetics, but re-naturalization/ecological servicing, heritage enhancement, and entirely new forms of urbanism, such as the “accidental wilderness” that is Tommy Thompson Park (1957 to present).

Against this transformative backdrop, the Ford government’s planned destruction of one of the city’s most distinctive, internationally renowned landscapes — Michael Hough’s design for Ontario Place — is both ironic and tragic.

Hough’s complex and layered achievement, though overshadowed in the public imagination by Eberhard Zeidler’s iconic modernism, equipped Toronto’s waterfront with a kind of Olmstedian landscape that should be every bit as sacrosanct as the city’s landmark buildings, from the Ontario Legislature to the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts.

And yet we’re about to witness its demolition at the hands of both the province and the City, much of it razed to make way for a mega-spa whose over-weening design — by Diamond Schmitt Architects, which should never have taken on this commission — can at best be described as attention-seeking.

Born and educated in the U.K., Hough had a career that straddled two phases of landscape design. When he came to Canada in 1959, there were scarcely two dozen landscape architects practicing in Canada. His work at Ontario Place, as DTAH partner emeritus Robert Allsopp explained at a colloquium on the future of the site, was informed by both the ideas of landscape picturesque, but also contemporary concerns, such as the use of native species, now a table-stakes choice for any such project. “He was really ahead of his time,” adds Architectural Conservancy of Ontario director Bill Greaves, who is also a member of Ontario Place for All.

Hough’s professional legacy includes the landscaping for the University of Toronto’s Scarborough campus, the Humber Bay Shores Park in Etobicoke, and an early pass for the brickwork’s transformation. (He also taught at York’s Faculty of Environmental Studies for many years.)

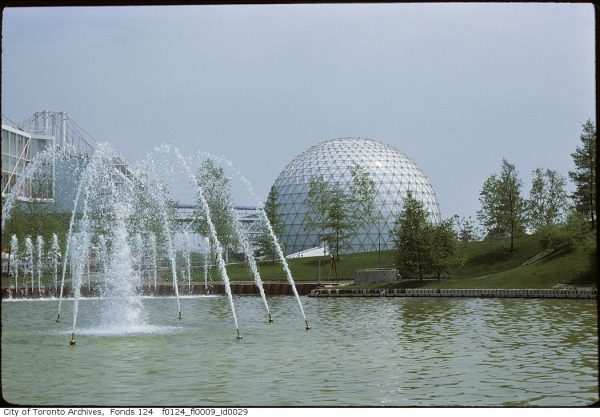

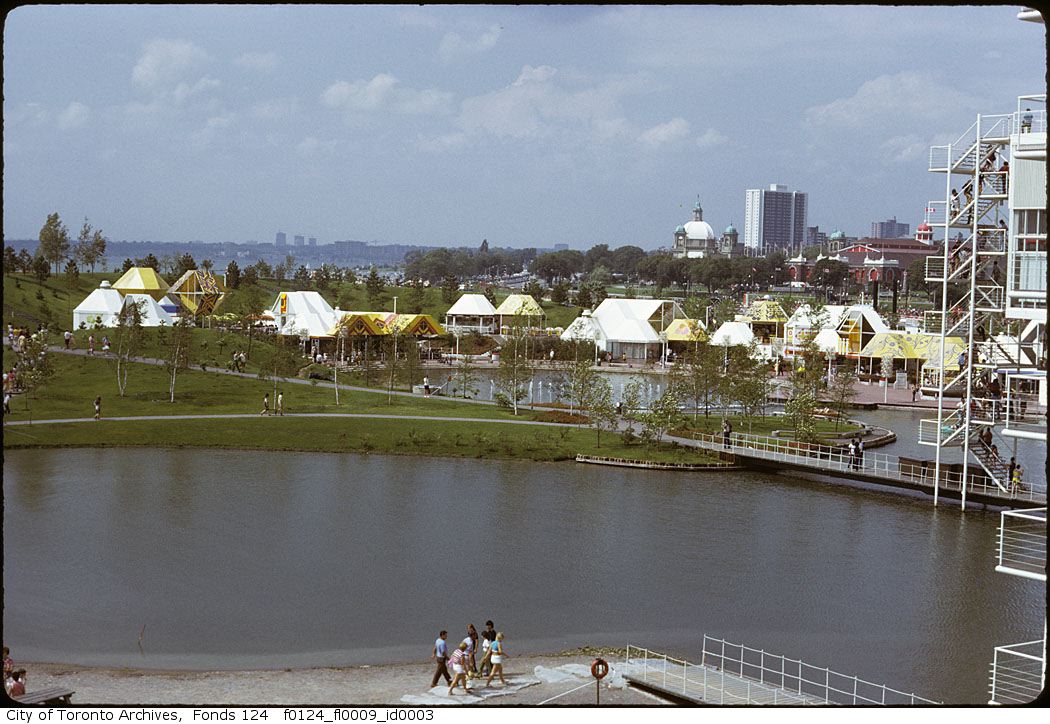

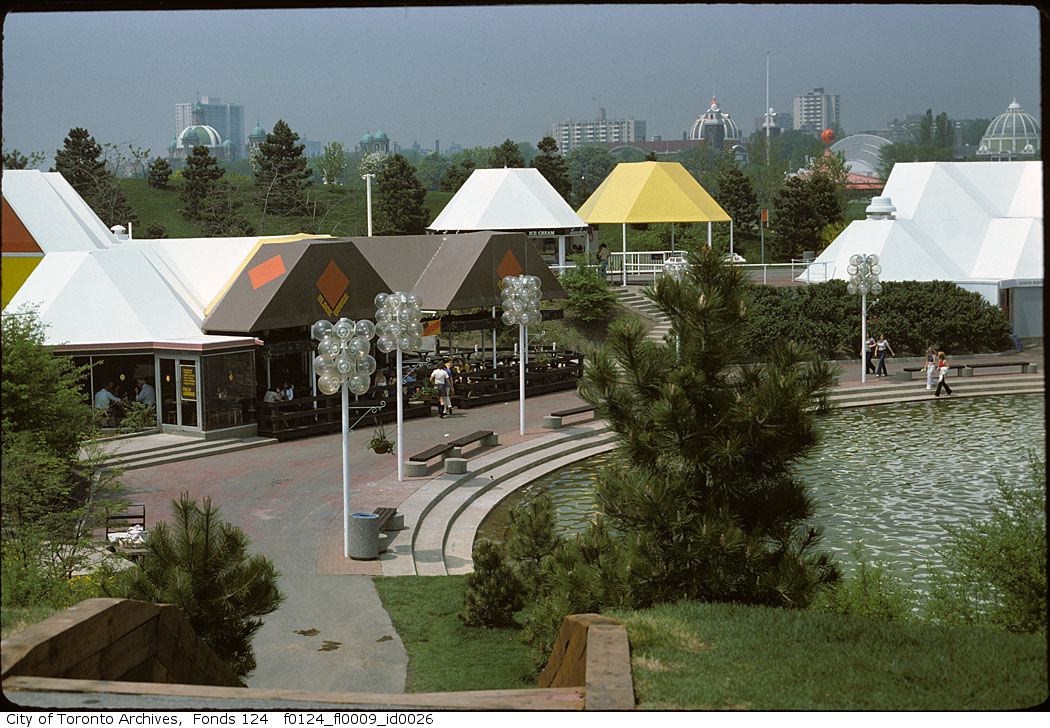

The landscaping for Ontario Place was rooted in practical concerns: protecting Zeidler’s proposed pavilions from the elements (waves, wind). The two islands, the so-called “grand” canal, and the hardened perimeter that skirts the southern edge of Ontario Place, were constructed as a shield. As Allsopp explains, “The profile of the berms and planting of the West Island are shaped, through wind-tunnel testing, to optimize the sheltering effect of the leeward areas that Michael refers to as the “quiet environment of parkland” — areas suited for more intensive recreational activities and the immediate aquatic setting of the principal hi-tech building structures.” (Hough describes his thinking about the design in this video of a lecture he gave in 1979.)

Greaves adds that Hough balked at later maintenance practices, such as excessive lawn-mowing. “Part of the design was for it to be somewhat wild.” It seems likely that Hough, who died in 2013, might have approved of the way parts of Ontario Place have become enticingly overgrown in the decade since the Ontario government shuttered it as a struggling theme park.

Allsopp says Hough created “a landscape that is appreciated through movement,” and through the sequencing of new vistas and compositions that reveal themselves as pedestrians move through the network of paths, canals and open spaces. “It is a game of tantalizing visual tease — of hiding and revealing — of enclosure and opening-up.”

Like Olmsted’s Central Park, Ontario Place’s landscape has also revealed itself over time, as trees and other plantings mature. Completely besides the sheer ecological folly of clear-cutting a half-century’s worth of forest cover that’s grown up on both islands (which is almost certainly what’s required to make room for the Therme spa and the Live Nation concert venue), the so-called redevelopment plan is erasing a landscape that has finally hit its stride.

The prospect is no less ridiculous and offensive than chopping down the oaks on the north end of Queen’s Park to make way for a condo with easy access to the Museum subway.

Unlike historically significant architecture, landscape design is a bit like good editing — most people don’t perceive it as such, even when naturalized landscapes are entirely constructed. Years from now, people wandering the winding paths that abut the new Lower Don ‘ravine’ that traverses the Port Lands may not realize the space was, for decades, a lake-filled and heavily contaminated industrial site, and before that, well, lake.

In many important ways, Ontario Place’s biggest problem is that its owners have refused to leave it alone, and to recognize its genius as a public space. The demolition of the Amphitheatre, in 1994, marked the beginning of a protracted assault on Hough’s integrated landscaping, as consecutive provincial governments scrambled to figure out how to make Ontario Place earn its keep. The civic-minded design, and critical elements like the children’s playground, were elbowed aside in favour of franchised concessions and amusement-park style attractions brokered by the cronies who populated the Ontario Place board of directors.

The footnote on this story, of course, is the construction of Trillium Park, which was opened in 2017 and succeeded in transforming a parking lot at the east end of the site into a highly successful landscape of trails, Indigenous place-making markers, vistas and open spaces.

The design team, LANDInc. and West8, the Dutch design firm that has played such a transformative role in Toronto’s waterfront revitalization, found a way to push back against the relentless commercialization of Ontario Place and, in so doing, honour what Hough had begun. (LANDinc. continues to work on the current redevelopment, leading the open space design.)

While the connection remains a bit ragged, Trillium Park, and the William G. Davis trail, succeeded in suturing a critical rip in the waterfront pedestrian/cycling infrastructure, providing a tie from the Martin Goodman trail and Coronation Park to the spectacle of Ontario Place’s south seawall. It’s a connection that now extends east to Little Norway Park, the Music Garden, and Harbourfront Centre, and west to Marilyn Bell Park and beyond. Yes, the Goodman trail was contiguous before the construction of Trillium Park, but it traversed Ontario Place’s two immense parking lots, with an enjoyable view of Lakeshore Blvd. at its most highway-like.

And then the pandemic happened. Suddenly, we all had to go outside to socialize, exercise, re-centre, remain sane. As I’ve argued previously, and as Spacing has shown in its reporting on bird-watching and informal swimming activity at Ontario Place, the pandemic brought many new visitors to the site, drawn by the nature, the views, the benches, the pleasantly abandoned vibe of the attractions and, for a while, the drive-in theatre. Even though it was closed, Ontario Place again became a destination — a park linked, in all the ways that a generation of waterfront advocates have espoused, to the rest of Toronto’s lakeshore.

The development of the Therme spa, on the West Island, will almost certainly transform the peaceful outer edge into a quasi-commercial space, sought after by the operator. And even if there’s some enforced delineation between the public and private realm, the experiential reality of the pathway circumnavigating the West Island will be massively degraded, as the slope and forest that offers a natural buffer between the lake and the city will be replaced with looming glass walls and the human aquarium views of the spa-goers within. There’s no putting lipstick on this pig, in my view. (The Live Nation venue is scarcely better, and requires not only extensive tree removal on the east island but the filling in of the canal.)

Allsopp observes that the other end of this necklace of increasingly contiguous public spaces is Tommy Thompson Park, like Ontario Place, a landform entirely constructed out of lake fill and construction rubble, with an ostensible mandate to create a sheltered harbour, and which has evolved, on its own, into a thriving ecosystem of wildlife, birds and native species.

Would we think of constructing a luxury spa and a 16,000-seat stadium on the end of the spit? Of course not. The idea is ludicrous, and a political non-starter. It’s worth saying, over and over, that the most important explanation for Tommy Thompson park’s resilience is that decades of Torontonians have breathed life into this defiantly public, non-commercial space using only their feet and the tires on their bikes. So it should be with Ontario Place.

all photos courtesy of the Toronto Archives

Join Shawn Micallef and myself on a wander around Ontario this Sunday, Sept. 11, at 10am, at the entrance to Trillium Park.

One comment

The idea of taking something so iconic, that is enjoyable by all, owned by all, and just handing it to private business should be the kind of thing that brings down a government. We need more public space, not less, and Ford just has no respect for things he doesn’t personally use (cars, sports, pot) so we need to make it clear that we DO use these spaces, we DO care. If there was a “Save Ontario Place” rally (or series of rallies), I’ll be there