Forty years ago, Molson, Labatt, and Carling O’Keefe collectively owned 96 percent of Canada’s beer market. Their shared monopoly produced little experimentation with a reliance on traditional formulas. Beer was expensive, and weak, made with minimal hops and large amounts of corn or rice. The market imposed a reality of bland lagers on purchasers.

Carling O’Keefe went on strike in 1979, motivating the Troller Ale House in Horseshoe Bay to become Canada’s first “cottage” brewpub in 1982. Granville Island Brewing opened in 1984 as the first of two Canadian microbreweries. By 1989, there were 42 new breweries in operation across the country. By 2014, there were more than 500, and more than half of those were in British Columbia.

The market had dramatically shifted from watered-down product, intended to sustain a long shelf life, in favour of quality and variety. By 2011, the large commercial breweries held a 45 percent market share, a reduction by half in just 25 years. The big breweries were forced to innovate in order to compete, ahem, head to head. That included purchasing upstart microbreweries outright or introducing new labels that suggested independent production.

None of this happened without advocacy by the beer drinkers themselves. The Campaign for Real Ale Society British Columbia was incorporated in 1985 and by 2013, its lobbying had helped bring about provincial laws making it much easier to operate a small brewery with tasting rooms.

Beer in B.C. is better for it, no doubt.

Let’s compare the liberation (or more aptly “imbib-eration”) of the beer market with today’s housing market.

The machinery and rules of various city halls favour big projects produced by big developers. This culture of “big approvals” produces rezonings, which generate Community Amenity Contributions that augment the public purse, which in turn keeps property taxes low. In Vancouver, such expected CAC revenue is so hardwired into development approval processes that it is an actual line item in the municipal budget. Does this put elected officials in a conflict of interest at any public hearing when they vote on projects that contribute to their own approved annual budget?

The city’s four-year election cycle further solidifies the “big approval” culture at city hall, because re-election campaigns rely on “What I have done for you lately” self-promotion. Politicians vie to claim they have kept property taxes low.

But like watered-down beer, the “big approval” approach to development in Vancouver deprives us of tasty alternatives.

For example, “big approvals” require assembled sites, which necessitates huge capital investment. But bigger isn’t always better, or more liveable, or cheaper.

A lot of big project money, because of bylaws, must be spent on storing cars underground. That adds to bottom-line costs, which in turn erodes housing affordability.

Remember when ads by big beer makers flooded our television screens? Similarly, big projects by big developers almost always include marketing “systems” that the end purchaser is obligated to pay for in the purchase price or rents. Fancy slogans, thematic project naming, luxurious presentation centres with high-end kitchen cabinets and granite countertops, and photo-simulated views from the staged display suite, celebrating the “good life,” all cost money. What is the value add of this soft cost service to the end-user, especially when life savings are being invested? Why do we continue to accept this reality as a necessary cost of doing business?

Further, and more specific to Vancouver, there appears to be a policy bias against “smallness.”

For example, while there has been some expressed support for “Missing Middle” experimentation, very little has actually happened towards piloting new, more innovative housing forms that do not require land assembly, underground parking or excessive marketing.

My understanding is that senior staff regard five-storey apartment buildings, now generated under the Moderate Income Rental Housing Pilot Program, as somehow representative of experimenting with delicious and even quirky alternatives to tall towers or detached homes. MIRHPP, and market rental initiatives, should be an innovation opportunity to introduce “Missing Middle” forms of housing. But building five-storeys or much taller, as recent MIRHHP approvals have greenlit, requires land assembly and have in many cases produced chunky forms that disrupt rather than enhance the neighbourhood fabric. This could not be further from “Missing Middle” designs presented in a recent competition by the Vancouver Urbanarium Society. Those building types are like craft beer delicacies — rich and diverse and nuanced. Have a taste.

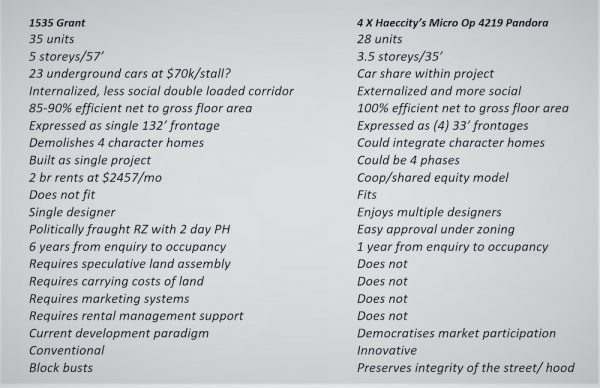

Let’s compare the Urbanarium competition’s innovative Missing Middle winner — 4219 Pandora Micro Op by Haeccity Architects — with the recently approved five-storey market rental project at 1535 Grant St.

Here is what was approved by the city:

Here is what won the Urbanarium competition and gives a sense of what could be there instead:

Now let’s compare what each does or would deliver:

Whether in their housing or their growlers, people want choice, diversity and value for hard-earned money. Is our city the best it can be by only emphasizing big projects produced by just a few influencers who know how to exploit the system? The current development paradigm, characterized by just a small cohort of established players, continues to impose the same old housing forms (diluted lagers) mandated by an archaic set of policies (planning bylaws and overlay housing policies) that suppress advocacy and entrepreneurial spirit.

A more democratized market, with many more innovators (smaller developers/builders/landowners with artisan sensibilities) who do not need to assemble land, is required to motivate housing innovation — just as occurred with microbreweries.

Vancouver’s politicians and planners should take a lesson from this province’s craft beer revolution. As with microbreweries, it is time for more micro-ops. It is last call on affordable housing so time to step up and raise the bar by ordering up a round of experimentation that could brew a tasty market for the next 30 years (the housing equivalent of a really hoppy double IPA). Cheers.

***

This piece was originally published on The Tyee.

***

Scot Hein is an adjunct professor in the Master of Urban Design program at UBC. He was previously the senior urban designer with the City of Vancouver.