“To Serve and Protect” – The Before Times

Our shared affordable housing challenge is becoming a wicked problem. We’re not there yet, but will be soon if we collectively allow land to further escalate in an undisciplined way. The complex, and interrelated, set of political, social, regulatory, and economic variables associated with our housing crises means that long-lasting solutions must be conceived in a holistic way: one that considers all the variables at once.

We must imagine the challenge as a “design problem”, requiring integrated approaches that simultaneously address multiple interests. And as with design engagement, if thoughtfully managed as a creative process, there is a chance of revealing more elegant outcomes that innovate and strengthen our communities instead of conventional approaches that tend to isolate respective interests.

I recall a large meeting where Vancouver City Hall departments convened to remind each other of their roles. The senior rezoning planner stood up and started his presentation with these words, “We Serve and Protect”. He was talking about neighborhoods, small businesses, and the greater good. At that time, the culture at city hall was careful, disciplined, proactive and aspirational.

It was a place of ideas.

Senior managers encouraged staff to bring their best every day, to be inventive, to challenge conventional ways of thinking and doing. We were invited to innovate, to even be entrepreneurial! There was shared pride in serving the public (I know there still is).

We were part of something bigger as we “practiced” proactive problem solving with peers across departments and disciplines. We learned from each other every day. Better ideas could come from anyone: I remember our Engineering and Parks colleagues having better urban design ideas about certain aspects of the Olympic Village.

We were inventing integrated city-making on the fly and leading by example.

We had sophisticated zoning tools to enable our work. A highly discretionary approach to regulatory approvals meant that every site seeking development permissions received sufficient attention to understand how a proposal might strengthen its context and deliver local amenities. Thoughtful development approvals, through creative and proactive engagement with the market, could enhance the lives of those who lived and worked nearby, while remaining decently profitable.

Design engagement/negotiation focussed on optimizing all interests. I also refer to this as “the elegance of discretion”: a policy-making and development planning culture at city hall that we practiced each day with rigor and care.

We served, protected, and improved our city each day by shaping the market.

We still had big challenges. In fact, many of the same challenges we have today, including social justice, poverty, homelessness, missing women, and drug addiction. To be completely honest, we were not serious about indigenous rights at that time. Something that is slowly changing for the better now.

These challenges were in stark contrast, however, to an emerging transfer of wealth into fewer and fewer hands. But from a regulatory standpoint, there was a delicate balance in the force. The market was profitable. The cost of housing had not yet outstripped income levels. Neighbourhoods were being methodically planned reflecting meaningful local insight, albeit too slowly for some elected officials, who make decisions based on four-year election cycles.

We routinely briefed Council on what we were up to. Senior Administrators steadily managed so that the development and building approvals process remained timely and predictable. Debate on both sides of the aisle was invited to occur transparently in council chambers with the city manager carefully navigating fractious politics while maintaining an optic of neutrality, and a champion for best practice. Our managers recognized and did not hesitate to sponsor, the best ideas/advice from the bureaucracy, the community, and the market so they could be debated.

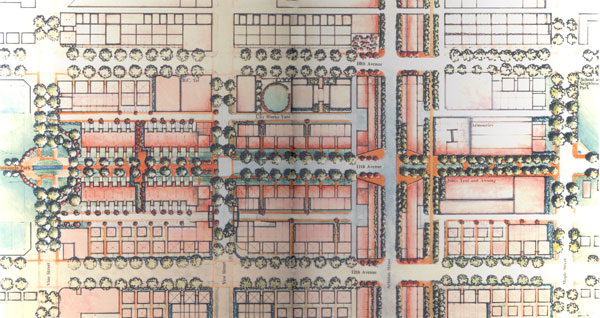

The consensus Urban Design Plan for The Arbutus Industrial Lands above, for example, was borne from a single drawing made by the Kitsilano Community. Planning leadership embraced this work—which proposed more than tripling prevailing densities—and negotiated a mutually acceptable urban design framework that reflected all interests while remaining highly profitable.

This consensus plan saved The Fraser Academy—a school for students with dyslexia and language-based learning differences—at the direct request of the neighborhood. There is legitimate social housing, and modest rentals for aging in place seniors. There is a local shopping street that has become the heart of community life. The local greenway, an idea from the neighbourhood, is regarded as precious open space amenity.

The special “pedestrians first” streets (also known as “Woonerfs“) were also an idea from the community. The plan generated productive economic wealth that made Kitsilano more resilient. Despite a packed Kits High Auditorium, the public hearing had only a few speakers expressing consensus support from all stakeholders.

This stands in contrast to how City Hall conducts business today: showing little interest in the recent consensus Urban Design Framework created by False Creek South (FCS) residents. A framework that aggressively increases density in support of inter-generational amenity, and housing for more families, all towards enhancing community resilience. The work of the FCS community is generous and forward-thinking and must inform the City-Wide planning process as it demonstrates how meaningful engagement can produce thoughtful outcomes.

In those earlier days, if Council did not agree with staff, that was ok, because we all learned. To serve and protect meant the constant invention of new best practices. We were the center of the regulatory universe with many cities from around the world beginning to emulate our best practices. Even academic books—like John Punter’s The Vancouver Achievement—were being written about us!

Then we ran out of land. The planning culture began to change. We stopped serving and protecting. We turned our back on the community. We began to lose our way.

The Decline (“declining to serve and protect”)

Today’s “business as usual” feels much different with the development industry’s influence snuffing out better housing approaches based on not-for-profit values. Really good ideas, that will save many folks a lot of their hard-earned salary, are not given sufficient bandwidth. And to make it even harder—as a consequence of administrative changes made almost 13 years ago—various departments don’t talk to each other nearly as much as they used to.

Instead, respective departments attempt to solve affordable housing as a “silo-ized” process that ignores more integrated potential for productive city-making. This makes it hard to gain a deeper appreciation of how our site-by-site discretionary approach to development regulation—more akin to the “Before Times”—can reveal new approaches to housing and tenure currently not produced by our market and critical to addressing our crises. This will be discussed further in Part 4.

We need to directly challenge the current political momentum of “let’s re-zone our way to affordability” by demonstrating new, more productive (better/faster/cheaper) housing outcomes available to the market by updating current zoning to be more socially relevant. Political recognition of counter-productive economic constraints on the cost of land, and their downstream impacts on housing prices and rents, must immediately compel new strategies for inter-generational reliance, shared equity, and enhanced social amenity—all necessary if we, as a city and a region, are to be resilient.

It’s time to question re-zoning as the primary means of delivering affordable housing.

The City’s bias for a constant revenue stream (Community Amenity Contributions or CACs) to augment municipal budgets and keep property taxes low must end. Re-zoning our way to affordability invites everyone to join the “profit party” which escalates land costs. This self-defeating approach rewards speculators at the expense of those who need affordable housing.

Re-zoning takes forever and is very expensive. Developers must hold onto the land over many years of city hall approval time with these costs passed on to renters and purchasers. And to make costs worse, the city’s parking by-law demands expensive construction of way too much parking at $70k/stall. Renters or new owners have no choice but to buy a stall, whether they own a car or not.

For many, it’s like giving away a full year’s salary for the privilege of living on top of a huge concrete bunker, or being told you must purchase an expensive sports car that you will never be allowed to drive, as your ticket to renting or owning housing in the same building. These costs, in addition to others such as thematic project marketing, must be offset by charging higher rents or purchase prices. This is why city hall promotes, under the current way of doing business, almost $4000/month for a 3-bedroom apartment as “affordable rent”.

This is also why I lose sleep.

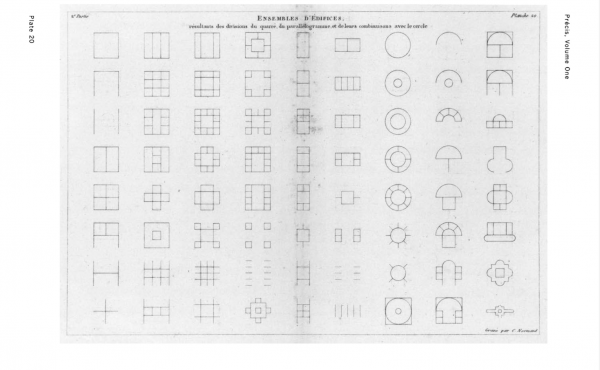

There is a better way…..zoning must evolve to enable more affordable housing that better reflects societal need. We can do this by introducing more productive building types with a greater variety of residential tenure enabled through more thoughtful discretionary regulations!

To be sure, there are pockets of innovation out there but little interest by political leaders or their staff to truly embrace this prospect. They, instead, remain focussed (read “Dazed and Confused”) on hard-wired, for-profit self-interests, that rely on big projects to sustain themselves. We simply can’t afford the societal cost of doing “bigness” this way any longer.

Instead—inspired by The Before Times—we can serve those left behind by thinking “small”, by not promoting land assembly, by not building underground concrete “car vaults” unnecessarily…..by not regulating in a way that removes over 50% of Vancouver land from more productive social contribution.

Please, no more single-family land hoarding!

Instead, let’s share our societal wealth with everyone in a way that strengthens our neighborhoods and builds resilience. After all, taxpayers own zoning, and it is zoning that is the “currency of affordability”.

***

Related articles, in sequence:

- You Forgot About Me! – Part 1

- You Forgot About Me! – Part 2

- Zoning Must Evolve – Introduction

- Zoning Must Evolve – Part 1

- Zoning Must Evolve – Part 2

- Zoning Must Evolve – Part 3

- Zoning Must Evolve – Part 4

- Zoning Must Evolve – Part 5

- You Forgot About Me! – Part 3

**

Scot Hein is a retired architect, former senior urban designer at the City of Vancouver and the University of British Columbia. He is an adjunct professor of Urban Design at UBC, lecturer at Simon Fraser University and founding board member of the Urbanarium.

One comment

That’s a lot of words for “I miss when you could be racist, and classist”.

I hate to break it to you, but the poors you hate so much are coming.