By: Helena Grdadolnik

Workshop Architecture provides public art consulting for the Toronto Transit Commission, Infrastructure Ontario and various municipalities and I lead much of this work. When people hear about this component of our practice, they picture me visiting art fairs and studios to hand-select an artist or artwork for a new station, building or public space. The reality couldn’t be farther from the truth. My role starts with crafting the process to select an artist, which is a tricky act of following public rules for fairness and transparency while trying not to shut down opportunities to allow the best possible artistic outcome.

In Canada the public art commission process most often used consists of two stages. In the first stage an open call goes out to artists asking for their qualifications and experience. Shortlisted artists are selected and paid a stipend in the second stage to develop an art proposal. These are evaluated by a jury of art professionals and project stakeholders, and reviewed for technical requirements. In many municipalities, this process is codified in a public art policy that makes the two-stage call the only option rather than one possibility for commissioning artists.

WHY THIS PROCESS?

The public art process and policies that back it up were established in Toronto in the late 1980s at a time when public art projects had zero transparency, and they were since replicated in many other Canadian cities. The policies brought good changes: decisions were no longer personal or political; artistic merit is now evaluated by people with appropriate expertise; and artists are paid for concept work.

The process – unchanged for close to three decades – also has some downsides. I confess, I have some issues with the two-stage process, but at times have no alternative available, so I, and other public art professionals that I know, have developed hacks and workarounds to make up for the system’s shortcomings.

WHAT DOESN’T WORK

During the second stage competition, to ensure fairness, artists are prohibited from working with the stakeholder team and community during their art concept’s development. As discussion is not allowed at this crucial stage, the artist needs to second-guess what the client, community or jury members want to see. This puts socially-engaged art practices out of the running by nature of their consultative and inclusive artistic process. Also, process-driven artists don’t fare as well as object-makers. This isn’t a judgement that one way of working is better than another, but a desire to open up the narrow field to a wider variety of possibilities and a larger artist pool.

OPEN AND INVITED CALLS

There are times when an art opportunity is very specific and would lend itself to certain artists, based on their ongoing research, experimentation or formal approach. In these instances, a curated selection would be beneficial but government purchasing rules state that commissions over $100,000 in value must be subject to an open call. It is possible to send the open call directly to relevant artists asking them to apply. This can help, but there are many artists who refuse to go after work in this way – either because they do not need to compete for new projects, or because they don’t feel their artwork or approach would fare well in this commissioning environment.

I developed a new public art program for the City of Mississauga in 2010. For one of the City’s first major public art commissions – the centre of a roundabout near City Hall, I was worried that we would not receive the caliber of artists and the specific skills we were after so I opted for an invited call. As the project budget was $250,000, we could only run an invited call if we separated the artist’s fee from the construction of the art. The company constructing the work was hired separately through an open tender process. To develop the artist longlist, I worked with curators at the Art Gallery of Mississauga, UTM’s Blackwood Gallery and Mississauga Arts Council to research and compile ten artists to invite to this opportunity. When inviting the artists, I still had a lot of work to do to convince a few of them to send their portfolios – including Michel de Broin, the Montreal-based artist that the jury ultimately selected. Using an invited call for this project set Mississauga off on the right foot and the City’s program has continued to develop its public art vision through a variety of strategies.

![Possibilities by Michel de Broin, Mississauga, a sculpture of seven coloured arrows inspired by roadside signage from the golden age of the automobile [courtesy: City of Mississauga]](http://spacing.ca/toronto/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/10/2-Possibilities-by-Michel-de-Broin-City-of-Mississauga-600x401.jpg)

Asking for curatorial proposals through an open call would be an even better way to move forward, but a harder sell to public bodies. This was the process used for LandMarks2017, a project that will see artists ignite a conversation about Canada at 150 in Parks Canada sites across the country. I have been advising the non-profit Partners in Art on this exciting project since 2014. Last November five curators were selected through an open call. Their proposals already included artists they were considering. Once they were on board, the curators worked together to refine their selections. The project has developed a strong indigenous focus and some fruitful collaborations that would not likely have come through if we had instead run an open call for artists.

A curated approach isn’t only beneficial to the selection of artists, but also during a project’s development when artists need to be challenged and supported. The diminished artist-curator dialogue may be one of the factors contributing to why some talented gallery artists, when faced with a public art opportunity, aren’t able to translate their work successfully into a public setting.

A ROLE FOR GALLERISTS?

I managed an artist call recently for the TTC where, for the first time, I saw a private gallery supporting their artists to move into the public art realm. Because this is not common in practice, the jury at first weren’t sure what to make of it, but concluded by supporting the practice (there is nothing precluding it) – and they shortlisted the artists in question. I would encourage more galleries to provide this service to their artists, since they may be more used to wading through the paperwork involved in a public art proposal.

ARTISTS ON A DESIGN TEAM

Another selection method available is a one-stage selection where a jury evaluates an artist based on their experience, approach and fit for a public art opportunity. The development of the art concept happens after they are contracted for the job. If you hire an artist early enough in the process, they may even be able to have influence on a project’s overall direction rather than responding to a place already marked on a site plan.

Years ago in England, I was an advisor on a pilot initiative called Artists & Places which funded artists’ involvement during the masterplanning stage in large development projects. After four years of funding, the project was disbanded in 2008, but the program was influential. Hiring an artist during the planning stage of a development and working with them over a number of years became a widely used practice, and was able to count towards a developer’s requirements for Percent for Art, a practice that should be considered for Toronto developments where art is sometimes an afterthought or the art opportunity is overly prescribed.

This thinking and approach to public art has been slow in moving across the ocean to Canada. One place that should be commended is the City of Calgary with their Watershed+ program. They selected Sans façon as the lead artists from an open call in 2008. Since then Sans façon have collaborated with the water authority on the creation of sculptural drinking fountains attached to fire hydrants for public events, a responsive LED façade of a lift station and the design of a park that doubled as a natural stormwater management system. They also identify opportunities for a range of artists to work alongside them in the program.

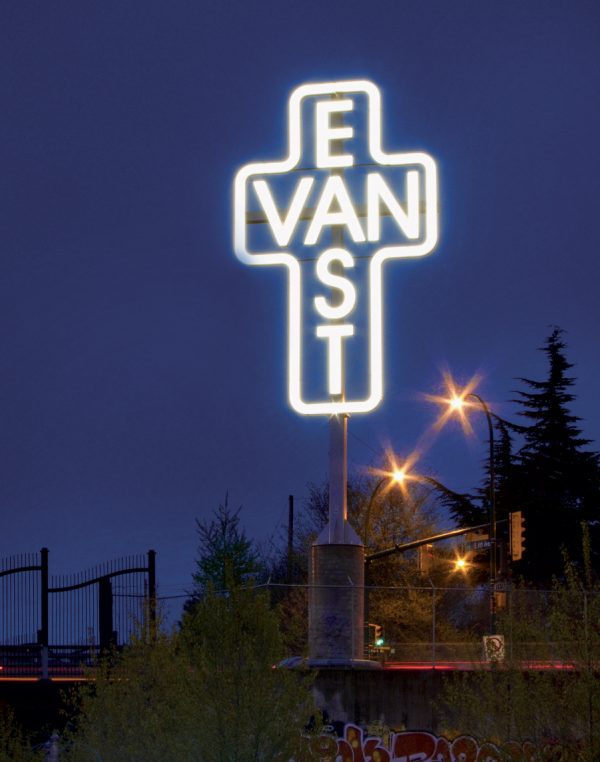

ARTIST-INITIATED

All the examples above show processes where the site is already determined to a greater or lesser extent before the artist became involved, but artists themselves are a great resource as ideas generators. Funding for public art is often tied to a place through planning negotiations. Where it isn’t, a call for artist-initiated projects should be encouraged. For the Olympics, the City of Vancouver ran a program called Mapping and Marking that asked artists to propose artworks based on their own ideas and art practices at public sites of their choosing. The result is some of the strongest examples of placemaking and public art I have seen in Canada, including Ken Lum’s Monument for East Vancouver.

SUPPORTING ARTISTS NEW TO PUBLIC ART

The question of how artists without public art experience can break into the field always comes up. There are a number of ways to tailor a call – either through what is accepted as relevant experience, the weighting of the evaluation components, or hiring based on a call for art concepts (a practice used by the Edmonton Arts Council for projects under $100,000). Selecting jury members with an open mind is also key.

As the commissioning process for artists is very different in a public procurement, the submission itself can be a barrier. For this reason, some municipalities provide courses, like Calgary’s Public Art 101, to train artists in how to respond to calls. In 2014 I ran a workshop with the Art Gallery of Ontario for the City of Toronto’s Out of the Box street art program. We had artists develop their proposals and then submit to the City at the end of the process. If so much work has to go into this training, maybe we should instead revise the commissioning process to suit artists’ practices?

RETHINKING THE PROCESS

The City of Toronto was one of the first in Canada to have a public art policy and program and they led the way for so many others in Canada, but their policy has not had a comprehensive review for almost 30 years. Thinking around public art has moved on around the world, but Toronto hasn’t moved along with it. It is time for Toronto to lead again in this area. Hacks and workarounds can only get us so far. We may need to be a bit more creative about the process, to get the creative outcomes we seek.

Helena Grdadolnik is a director of Workshop Architecture in Toronto, where she leads the studio’s urban design work, creative and cultural projects. Helena is a member of the Toronto Public Art Commission, the Public Art Network Advisory for the Creative City Network of Canada, and the Active Neighbourhoods Canada Advisory Group. workshoparchitecture.ca @WorkshopArch

The Artful City is a bi-weekly blog series exploring the evolution of public art and its role in the transformation of Toronto, both the city fabric and the community it houses. For more information about The Artful City visit: www.theartfulcity.org @ArtfulCity

One comment

Thanks for breaking down this process. I don’t think a lot of people get to see the professional processes around public art and design. It’s actually helped me to break down the city’s art engagement, in a more rational context.