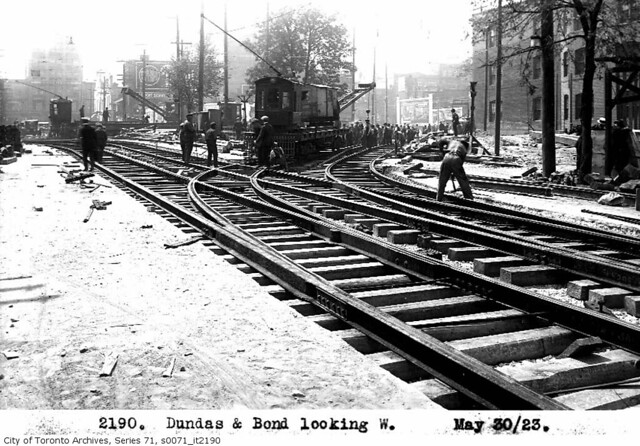

TTC work crews laying new tracks on Dundas Street Diversion east of Yonge Street in 1923, linking former Agnes and Wilton Streets, and in the process, creating the triangular parcel that later became Dundas Square. Image: Toronto Archives Fonds 16, Series 71, Item 2190.

![]()

Dundas Street is one of Toronto’s most fascinating roadways. While it runs uninterrupted for 23 kilometres between the Mississauga border at Etobicoke Creek and Kingston Road towards Scarborough, it meanders, crossing Bloor Street twice. Even in the downtown area, it makes subtle jogs near major intersections. As mentioned earlier, Dundas was built as a military road, Dundas Street kept a fair distance from the lake to be an effective alternative route in the case of war.

Dundas is not a solid commercial throughfare, despite the traffic and frequent streetcar service, unlike parallel streets such as Bloor, Queen, College, Danforth, and Gerrard East. Except in Chinatown, the only major strips of retail are west of Ossington in neighbourhoods such as Brockton, the Junction and Islington Village. East of Broadview, Dundas Street appears somewhat run-down and lifeless.

The Town of York was founded in 1793 with a perfect grid of rectangular streets. Yonge Street — with only a slight corrective angle north of St. Clair — is the origin of Toronto’s rectangular concession system and runs in a straight line from Lake Ontario to Lake Simcoe. Queen Street, originally named Lot Street, also runs in a perfect line between Humber Bay and the RC Harris Filtration Plant, forming the base line for the east-west side roads.

As the town expanded, the grid of streets was extended outwards, particularly to the west (the swampy mouth of the Don River precluded development to the east), and as the old Park Lots — the large parcels of land north of Lot Street were developed — long north-south roads, instead of the east-west street orientation to the south, were laid out parcel-by-parcel as they were sold off or developed by the lots’ owners, generally gentry and clergy. Today, the old Park Lot system has left its legacy in the jogs of Dundas Street, which has incorporated more vanished streets than any other in Toronto.

Dundas Street was originally built to connect Lake Ontario with Governor John Graves Simcoe’s planned townsite at present-day London. The road was soon extended east to Toronto, connecting to Lot Street (now Queen Street) at today’s Ossington Avenue, well to the west of old York’s townsite. A common misconception (one that I previously made as well) is that Dundas Street was named because it went to the town of Dundas. In fact, the town was actually named after the road.

Until nearly a century ago, Dundas Street still terminated at Queen Street while Ossington ran north from the Dundas/Ossington/Arthur intersection. Arthur Street ran east from there to Bathurst Street and terminated at a T-intersection. St. Patrick Street ran between Bathurst (at another T-intersection south of the corner of Bathurst and Arthur) to McCaul, where Anderson Street continued east to University Avenue. With another jog to the south, Agnes Street continued to Yonge.

East of Yonge, Wilton Avenue (originally named Crookshank Street) ran east to Jarvis, where it made a slight curve as Wilton Crescent to Sherbourne (near the present site of Filmore’s Hotel). In the 1910s, Wilton was extended across a new bridge, and incorporated Elliot Street on the east side of the Don. This 1916 map from the University of Toronto’s collection helps illustrate these former streets.

After the First World War, these various minor streets were connected to provide a new east-west throughfare across the city, from Toronto Junction and across the Don to Broadview. Jog-removal projects were completed at University and Yonge Streets, though the jog between former Arthur and St. Patrick Streets at Bathurst was not completed until after the Second World War. Not only did the project benefit automobiles, but streetcars benefited from faster, through routing. Indeed, the Toronto Transportation Commission built new track along Dundas and rerouted its services to take advantage of the new links by 1923.

Some of the old names that disappeared by the through Dundas designations were recycled: Wilton later reappeared as Wilton Street in the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood. William Street, which ran north-south west of University Avenue, was later renamed St. Patrick.

Interestingly, the remaining piece of Wilton Avenue left by the new Dundas Street Diversion between Yonge and Victoria Streets was originally named Wilton Square. It was later renamed Dundas Square, lending its name to the new public square created by urban redevelopment a decade ago.

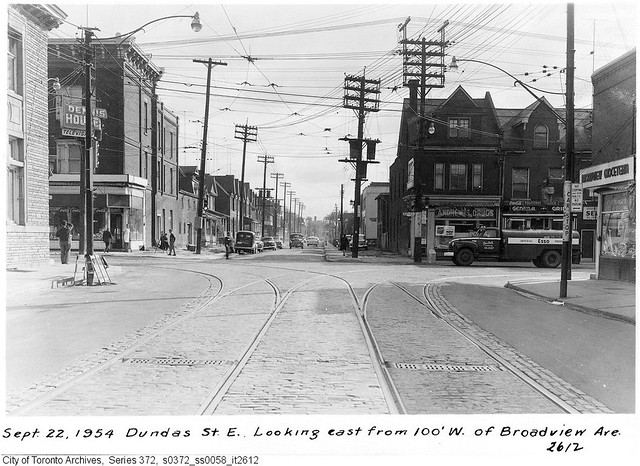

Dundas looking east to Broadview in 1954, just before widening as new traffic artery. Toronto Archives Fonds 200, Series 372, Subseries 58, Item 2612

But Dundas Street was still yet to be extended farther east. In the early 1950s, the City of Toronto began a new road project to extend Dundas eastwards from Broadview to Kingston Road to serve as a new four-lane traffic arterial, intended as an alternative to Gerrard and Queen. From west to east, Whitby Street, Dickens, Dagmar, Doel, Applegrove and Ashbridge Avenues as well as Maughan Crescent and Hemlock Avenue were all cleared and widened for this purpose. In some cases, alleyways were used to connect these nine separate streets, and this is clearly visible as garages and backyards continue to front on to Dundas near Jones Avenue.

Garages back onto Dundas Street East, west of Jones.

The increasing popularity of the automobile, as well as increasing pressures on the streetcar network in the 1910s and 1920s resulted in a number of similar rationalizations. Carlton Street was bent at Yonge to connect directly with College in 1931, though this was made possible and encouraged by the Eaton’s Empire who accumulated numerous land holdings in the area. Bay Street was directly extended north from Queen, incorporating Terauley Street (hence the curve at Old City Hall). North of College, the extended Bay Street jogged slightly again to connect with now-disappeared St. Vincent, Chapel and North Streets to reach Bloor; tracks built in 1923 on this new section of Bay relieved streetcar congestion on Yonge Street. Dupont Street was formed as a minor east-west arterial by combining it with Royce and Van Horne Streets (and entirely new sections of roadway), also in the 1920s and 30s.

The Metropolitan Toronto government, formed in 1954, did its part, extending Eglinton Avenue across the city, incorporating the previously disconnected Golden Mile in Scarborough and Richview Sideroad in Etobicoke. Lawrence, Sheppard and Finch Avenues received similar treatment. In the early 1960s, Duke and Duchess Streets, two of the original Town of York streets, disappeared as Adelaide and Richmond Streets respectively were extended east of Jarvis as one-way arterials to feed traffic to and from the new Don Valley Parkway.

Dundas Street certainly isn’t the only road to be rationalized by the city to facilitate smoother transportation, there are over a dozen more instances. But Dundas is the most remarkable in terms of its length and effort to link 15 streets together over four decades.

11 comments

Dundas ends at Kingston Rd but in old Toronto, not Scarborough, between Coxwell and Woodbine.

John: Of course. I had meant to write “towards” instead of “in”. I fixed that obvious error, thanks.

Regarding Dundas being named after Dundas Street, rather than vice versa: I’ve noticed that streets that head somewhere (historically) are labelled ‘road’. For instance, Kingston Road goes in the direction of Kingston, Markham Road to Markham, Weston Road to Weston, …

Queen St is not perfectly straight. There are subtle turns along its length. Between Neville Park and University, the offset is about 50m.

And the interesting thing about about Maughan Crescent is that it was just its southern tip subsumed into Dundas, while the rest of it remains–in effect, it was “overlapped” by Dundas…

I have seen achieve photos of Dundas Street West just west of Landowne Avenue to Sorauren Avenue, where instead of the streetcars running down the middle of the street, they shifted north to run on it own right-of-way. The right-of-way disappeared as the automobile took over the roads.

The City of Toronto Archives has posted a number of pictures of streetscapes on Flickr. Here (http://www.flickr.com/photos/torontohistory/sets/72157623947177932/with/4559608486/) is the link to the folder with pictures of Leslieville, including Doel Ave. (modern Dundas St.). My great grandparents lived on Doel, closer to the Kingston Road end, although I am not clear that their house survived the re-alignment of the street.

Dickens wasn’t incorporated into Dundas St E, it’s still around today

http://maps.google.ca/maps?hl=en&ll=43.664379,-79.34257&spn=0.002837,0.004823&t=h&z=18&vpsrc=6

The map you linked to is fascinating. In my own neighbourhood (Oakwood-St Clair) a number of streets are “missing” and Rogers Road seems to be just a shadow of its future self. Also really neat to see the streets that used to sit in the pocket where the Allen Expwy runs today.

Is the old segment that was St. Patrick the source for the name of the University line station? Or as others have noted from the old ward boundaries which predate the numbered system evident on the posted map? Then there’s the St. Patrick Catholic church on McCaul. Anderson would have been the historically correct name for the station, but St. Andrew two stops down on King might have caused some confusion.

This is very interesting. The 1916 map referenced is good, but has at least one error: at the current Greenwood Park, the mapmaker appears to have gotten confused with the area just to the west – notice the repetition of Sproatt, and other streets.

The map shows what is now Dundas on the south side of Greenwood Park continuing east past Greenwood, but that connection was not made until at least the 1940s. There’s a photo in the Toronto archives of 114 Greenwood (that intersection) in 1946. It shows a footpath in that location going west from Greenwood for approx. 2 blocks, it clearly wasn’t a street yet.