Over the next year, City of Toronto politicians and planners will be faced with an unprecedented challenge: how to create amenable public open spaces in and around a massive re-development proposal for the north-west corner of Front Street and Spadina.

Three developers — Diamond Corp., RioCan and Allied — have combined forces to spend an estimated $1 billion dollars to transform the 3.1 hectare block that has been home for decades to The Globe and Mail and a Toyota dealership.

The 2 million sq.-ft project, one of the largest proposed for the city’s core, is known as The Well, for its location on the historical block of Wellington Street West. The builders are proposing a mix of roughly half commercial (office and retail) and half residential to create what designers envision as this city’s version of developments like London’s Butler’s Wharf.

To accomplish this, the builders want to be trusted to provide, and take care of, most if not all the public amenities traditionally required as trade-offs for the development approval.

The consortium has already asked the city to drop conventional demands for internal roads through the project in favour of pedestrian walkways and bike paths. What’s more, the developers hope to forego the usual parkland dedication in exchange for an agreement to construct and maintain a network of privately-owned plazas and walkways that will be open to the public.

As part of the deal, which would ultimately enable these companies to build a series of large office and condo towers, they’d also like to landscape, and look after, adjacent sections of public land on Wellington, Front and the historical enclave of Draper Street.

Participants called the ongoing negotiations complex and delicate. How they end will provide the best look yet at to how the city views the provision of so-called privately-owned public spaces (POPS) in high-growth downtown districts. The policy, picked up from New York City three years ago, is intended to create a network of plazas, pathways and other open spaces that can augment the dearth of conventional parks in an increasingly dense downtown.

In New York, planning officials in the late 1950s began offering private developers additional height and density in exchange for light and public open space. This “incentive zoning” generated hundreds of plazas, arcades, walkways and pocket parks owned and maintained by property managers. New York journalist Adee Braun has described the Big Apple’s POPS as “urban nesting dolls [that] were built to provide the public with shortcuts, shelter and gathering spaces.”

Will Toronto’s POPS achieve similar results? Or is this primarily a public relations exercise that does little toward ameliorating the underlying problem?

Last week, Spacing revealed that hundreds of millions of dollars have flowed into parkland reserve funds, much of it from high-density development in the core. But while the city can point to a handful of new park acquisitions and partnerships, it’s struggling to invest in new public open space in areas experiencing significant population growth.

To counter those difficulties, city planning officials point to the growing inventory of POPS downtown, which, they say, have added a million square-feet of open space in the core since 2000. The planning department is also aiming to improve signage and encourage builders to create better open spaces at the base of their buildings, using tools such as site plan agreements.

Approving and promoting POPS looks good to this municipality. Piggybacking on — or expanding slightly — plans that developers already have in place, in exchange for a bit more height or density, appears to be highly economical. POPS, in theory, provide some of the benefits of public parks without requiring the city to maintain lawns, trees, gardens or infrastructure. What’s more, POPS can be built without depleting the city’s parkland reserve funds.

“As Toronto continues to grow,” according to a May, 2014, staff report adopted by council, “there is an increasing need and demand to create new parks and open spaces as places of retreat, relaxation and recreation that contribute to the health and well-being of City residents. As land values increase, however, it is not always possible to purchase properties to create new public parks in areas of the City that are most in need.” New POPS guidelines include classifications for past and future POPS, plus standards for access, materials, lighting and signage.

Yet there’s no consensus on the effectiveness of POPS policies. “Given the whole dysfunctional nature of what’s going on in PFR, I think the whole POPS thing has been relatively successful,” said a former city insider. But, he added, “POPS should never have been seen as a replacement for public parks.”

Indeed, POPS policy remains contentious even in its birthplace. Some of New York’s best-known urban explorers spent years scrutinizing POPS to get a sense of whether the city was selling its light and air too cheaply. William (Holly) Whyte closely examined these spaces, and compiled his findings in a 1980 book and related film called “The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces.” Almost a generation later, Harvard urban planning expert Jerold Kayden visited all 503 of the city’s designated POPS and published his findings in a 2000 study entitled, “POPS, Privately-owned Public Space, The New York Experience.”

Kayden’s research found that 41% of New York’s POPs were of “marginal quality.” As he wrote in an op-ed in the New York Times in 2011, many of Manhattan’s POPS “were and are practically useless, with austere designs, no amenities and little or no direct sunlight.”

During a panel discussion at New York’s Centre for Architecture last summer, Kayden also described a process he called “POPS creep.” Whereas advocates point to the beauty and popularity of successful spaces such as the Seagram plaza and Paley Park, about half of New York’s landlords are not in compliance with their POPS agreements.

Violations range from minor infractions (allowing garbage to pile up in the spaces), to making designated POPS space inaccessible or inhospitable (by removing seating or locking gates), and even enclosing and decorating POPS arcades so they become the formidably elegant lobbies of private buildings. New York has learned the hard way that creating and maintaining public space carries the usual caveat attached to offers of a free lunch, Kayden said.

Kayden, who runs New York’s own POPS database, has concluded that POPS policies pose three substantial dangers: they undermine zoning requirements; they signal to developers that zoning exemptions are for sale; and they are not equitable because, unlike public parks, few POPS are equally accessible to every citizen.

That hasn’t stopped many North American cities, with the recent addition of Toronto, from adopting and adapting a New York-style POPS policy. But this trend raises the question: if the results fall so far short of the mark in the city where this approach to public space originate, what chance will the policy have of working in Toronto?

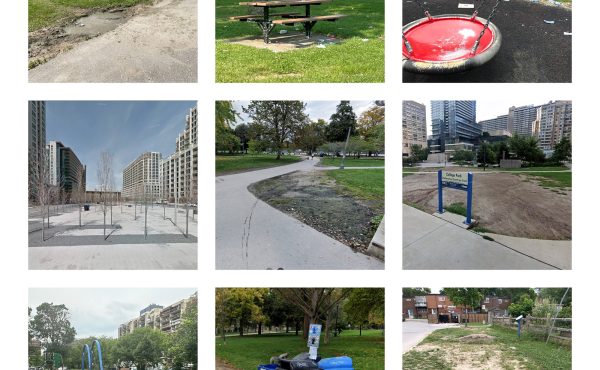

Spacing contacted people involved with The Well’s POPS approval, visited each of the approved POPS-designated sites and analyzed the City’s new interactive database. Our conclusion: at this juncture, Toronto’s 100-plus POPS fall short of establishing a network of high quality open spaces, and certainly don’t compensate for the inability of the city to use existing resources and regulations to create new park space in high-growth areas.

Some, certainly, provide iconic and well-used spaces, such as “the Pasture” between the TD Bank towers, or the fountain tucked between the wings of Commerce Court. A few have trees and ledges where people can sit to talk and eat their lunches. But many –including the new Iceboat Terrace in CityPark, site of last summer’s unveiling of the first POPS plaque, or the landscaped plaza in front of Tridel’s tower at 300 Front Street West — appear to be desultory, and offer few amenities to pedestrians.

Toronto architect and scholar Cheryl Atkinson — who has studied the history of POPS, as well as that of the Wellington West corridor — recommends that the city exercise a high degree of caution. POPS, she writes in a study pending publication in the urban studies journal Spaces and Flows, “are generally often perfunctory responses to an ever-diminishing, truly public realm in quantity, connectivity, and collective consciousness.”

What’s critically needed, Atkinson continues, “is a strategy for integrating public space of significant scale, continuity and impact into the highly dense core neighbourhoods where they may form a part of the daily social, cultural, and transportation network rituals of these communities.”

Everybody who agreed to be interviewed, on or off the record, conceded that POPS are not, and should never be seen as, a replacement for parks. City planners, however, defend the strategy. “POPS are important part of framing a city’s open space,” says James Parakh, manager of urban design for the city’s Toronto and East York district. At a recent Canadian Urban Institute’s symposium on place-making, he offered a series of current and future examples [PDF] showing how POPS can link downtown developments and networks of urban plazas.

The open space planned for The Well is poised to become downtown Toronto’s most ambitious POPS, and its evolution in coming years will be well worth watching. The developers are going to great lengths to appease the city’s requests for light and air: the latest plans include a complete redesign and repositioning of a 36-storey office tower to create 37 additional minutes of sunlight on city-owned Clarence Square.

A revised open-space proposal, submitted to the city’s Design Review Panel in late March, includes an ambitious internal network of landscaped gardens, pedestrian walkways, glass-covered seating, child-friendly water features and Parisian-inspired flexible furniture. It will include wide leafy openings to both Front and Wellington.

POPS space will be extended to open onto Draper and a cantilevered landscaped berm will turn public land on south side of Front Street into a multi-level public parkette. All together, the owners have proposed transforming 36% of the site — about a hectare — into new public open space.

It’s still a far cry from New York’s largest and most successful POPS, the Seagram Plaza, which takes up 75% of the site’s Park Avenue footprint. But by allowing The Well developers to create privately owned public spaces instead of insisting that they turn over land for a city-owned park, the city, The Well’s landscape designer Claude Cormier says, will receive high quality urban design and public accessibility without incurring the cost of construction and maintenance.

But what options does Toronto have? “There is no money to maintain a public park,” Cormier adds. “The city is limited in terms of what [it] can do.” He is optimistic, however, that this new synthesis of private vision and public access will produce the sort of great public open spaces that seem to be elusive under existing parkland funding mechanisms.

“This will be open urban space,” he says. “This will not be a mall.”

Seagram Plaza photo by Trevor Patt

Part 1: All built up but no place to grow

Part 2: Where the money flows

Part 3: The perils of cash-in-lieu

Part 3 sidebar: Section 42 explained

Part 4: The tale of two parks

Part 5: The system worked (slowly) for a west end park

Part 6: Are privately-owned public spaces the answer to parks deficit?

7 comments

To me, in the current climate, POPS seem like a bit of a necessary evil. They aren’t great, but really they are about as good as we’ll get until the city nuts up and spends some cash.

I don’t like when they are in the form of large plazas in front of properties (like is common in NYC and as in several examples in Toronto) they drastically breakup a uniform street frontage, and shift any at grade retail way back from the street (I presume impacting their commercial viability). Uniform street frontages are comfortable for people. (This is also a reason why breaking up street frontages with micro public parkettes instead of cash-in-lieu isn’t great either)

But I also don’t like that they aren’t necessarily permanent. If they remain in private ownership, they can always be requested for redevelopment by the owner and the onus is on the city to say no. Case in point, the NW corner of Yonge and Eglinton. IIRC, this formerly open plaza (which while not great all there was at the intersection in terms of open area) was provided in exchange for the city closing a street through the block to allow for the development. Fast forward to a few years ago when the owners wanted to build more retail on the plaza… and voila… no more POPS (and no, the new rooftop open space isn’t a satisfactory replacement… if takes an effort to get to it, it doesn’t count).

Use of public spaces in Toronto is already so tightly restricted by city rules and regulations. Do we want more spaces which are subject to the whim of private landowners as well?

POPS take the Public out of Public Space… what we are left with is just Private Open Space… a POS.

I remember the private/public raised park in St Jamestown. Fantastic idea until the condo owners suddenly realized that they were going to be sharing it with undesirables on occasion, at which point all “public” access points were removed

Can someone point to some successful POPS in Toronto? I have not seen any that impress me. Am I missing something? Seems to me just developers scams to get more density and leave the public without decent open public space.

As in NYC, Toronto needs to find a way to enforce violations of existing POPS policies. Liberty Village has a townhouse development with publicly accessible walkways that were closed off years ago with gates, but because the city’s Urban Design POPS group is taking many years to tabulate existing POPS, the vast majority can’t be verified by the city. I found out from the Development application and local planner.

I’ve also had a planner In North York request a property manager on HumberStone Drive remove the large ‘private property no trespassing’ signs aimed at a public walkway that provides a convenient link in a development where POPS paths were allowed to replace streets. The planner told me that property management ignored his calls, and he told me that the (at that time upcoming) city POPS program would solve these problems. It took me about a year of requests, to finally get this overworked planner to spend some time in the Archives and verify the POPS, but that’s the only way it can be verified since it’s not in any internet database.

Most property owners find legal ways to dissuade public use, for by example enclosing the space with arches, naming the space, not using public looking streets, adding stairs, not allowing through views so that a person can see that a path traverses the development, and placing multiple ‘private property no parking’ signs pointed at pedestrian paths. The ‘private property’ words are in big type, and would give most people the impression that they are trespassing. In law the sign is only supposed to be aimed at the (often unlikely or impossible) person who wished to park on the path or park space.

I see the line at the bottom of Toronto’s POPS map, “Access to some POPS locations may be refused in certain circumstances,” and it makes me cringe. These aren’t public spaces without a strong commitment to making them fully public. Of course, “in certain circumstances” access even to fully public spaces may be refused; but the disclaimer on the map suggests spaces that are less than, possibly much less than, public. POPS can only serve as adequate public-ish spaces to the extent the city and their owner/operators strive to keep them fully public.

As the article seems to point to, POPS can have some benefits and are usually better than nothing, but generally they shouldn’t be thought of as substitutes for public parks, streets and connections. While some developers and property owners embrace the concept, most will be constantly working against public access. The city neither has the regulations or the manpower to make private owners fulfill the goals of public park space and access. The Well is an example of a replacing public with private.

One of the best examples of a POP was the parkette which stood at the corner of Bay and Dundas Streets for over two decades, owned by the developers of the Eaton Centre. It was used by thousands during the day, but at night a desolate no man’s land. In my book (A Life in the City, http://www.smashwords.com/books/view/175179) is a chapter which deals with the park and some of the stories around it. POPs can be good, but they can also be abused and bad.