Interview by: Melanie Fasche

Sean Martindale is a Canadian artist and designer currently based in Toronto. He holds a Master of Fine Art from OCAD University, Toronto, and a Bachelor of Design from Emily Carr University, Vancouver. Sean’s playful works question and offer alternatives for existing public spaces, infrastructure and materials found in the urban realm. His work activates public space to encourage engagement and prompt conversation and interaction.

Sean’s body of work includes public interventions, works for exhibitions and festivals and more recently community-based projects. His work has appeared in galleries and museums, festivals and on the streets worldwide in cities such as Berlin, Hong Kong, London, New York, Montreal, Paris, Shanghai, Toronto, and Venice. He works with Katzman Contemporary in Toronto.

We met with Sean at a downtown café to talk about his art practice and perspective on public art in the city.

Melanie Fasche: Let’s start by talking about your motivation to create public art.

Sean Martindale: There are many reasons why I started working in public spaces. From a young age other artwork in public, like graffiti or accidental things that are not necessarily artwork – for example a glove found on the street and put on a pole, so it looks like the pole is waving at you – caught my attention and made me want to create works in the public realm. I like that public art is free for anybody to see and that it is not as intimidating as work presented in art galleries, which may be because the artwork is in our natural environment. Public spaces are where politics exist, and addressing issues where the issues are situated, for example environmental questions, or the privatization of public spaces, is part of my interest in working in public.

Much of my work is ephemeral. I like seeing how artwork lives in public spaces. I am putting something out there, but I do not say this is how it has to be or should be, it is just a possibility. I like to see if somebody tears it down or weather destroys it, or if people embrace and protect it. I like the accidental audience. I have interactions with people, sometimes while creating the work, sometimes afterwards, sometimes they don’t know I created the work. I think that this ambiguity of who created it and how it is created adds to the experience and can make people pay more attention to it. For example, the work where I had the grass spilling out of the planter, some people knew it was an installation, and others thought, “Look what happened, the grass has been growing in a way that makes it look like it is spilling.”

MF: In addition to your ephemeral projects, what are the other types of art that make up your body of work?

SM: My public art practice includes different areas that I work within, from public interventions, works for curated public exhibitions and festivals, community-based projects, to permanent public artworks; although the permanent artworks that I have created so far are still mural or wall-based projects, they are not the free-standing public artworks you may picture.

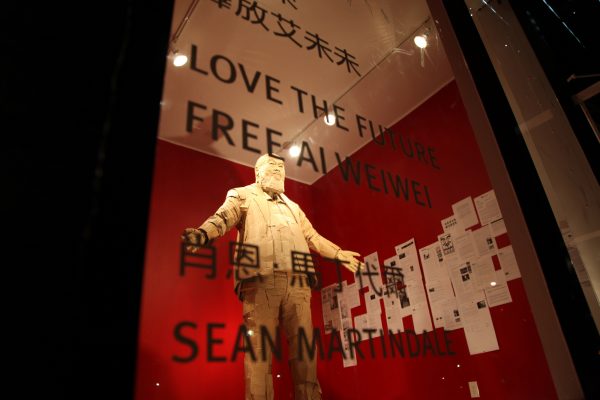

I have also shown in galleries and I have sold some work. In most cases people came to know my public practice first and then invited me to do shows in galleries. The work I have shown in galleries was either specifically created for those spaces, like the Ai Weiwei piece, or tied back to something I had done in the streets, for example my photo-prints and videos documenting my public interventions. But my drive and thinking in creating new work has always been doing projects primarily in public space.

MF: Are there differences in how these different types of works are created?

SM: All these differ in ideation, form and the final result. For my public interventions sometimes my ideas are triggered by the site or a piece of infrastructure, for example the poster pockets, the concrete planters, or using chain-link fencing. I see something in it, a potential that is not being met, or it might tie into a particular issue that I am interested in addressing. Other times it comes from an issue that I want to talk about, oftentimes those are political issues, and I think of where and how I can best talk about it, and then the material and the site comes from that. But no matter where the idea comes from, I consider my work carefully before I put it out into the world. I always ask myself, “what am I saying by doing this, what dialogue can I open up?” although you can never fully predict what happens once the work is in the public.

For commissioned works I am usually presented with different site options, for example when I do a festival like Nuit Blanche, but sometimes it is very specific, a small zone or room to work in. Then I look at the context of the particular space, the history, the current politics of that space, the physical properties, lighting, and weather. I go through a lot of the same processes, but it does not come the same way as when I am walking around and thinking about an issue and coming up with an idea independently. With commissioned works I am presented with something and often asked to solve a problem, although it is not always clear cut as in, “this is the question, this is the problem, this is the solution,” it is not as cut and dry as a design problem.

Both my public interventions and the commissioned works are political and talk about specific political issues. Although both tend to be ephemeral or temporary, I always hope that the conversation will last.

When working with a community the creation is different because I am working together with a group of non-artists or emerging artists. The idea for those projects can be generated to different degrees from my own influence. Sometimes the intention will be to get as many ideas from the group as possible, and as little from me. Here my role is to facilitate, to inspire them and give guidance and get the ideas flowing and the conversation going. Often it is more of a collaboration or co-creation where my ideas are welcome and a big part of it, and sometimes it is more of a mentorship model, where the project is mainly guided by my ideas and I show them ways of doing it, answer their questions, and help with the physical creation.

The community-generated works are usually more permanent, and their direct involvement plays a major role in whether that community embraces the artwork or not. I have observed art projects led by others and created without any community involvement where the community has come to love and embrace the art, but I have also seen cases where the artwork has been dropped in and the community does not like it. I feel that sometimes residents are justifiably protective and skeptical about the art coming in because they recognize it can be a sign of gentrification, and it becomes a problem, a political issue. I think as an artist you always hope your artwork will be embraced by the community, but again, you can never fully predict what will happen, there is always a risk.

MF: We are curious to learn more about the process of co-creation in your community-based projects. Could you describe the process in more detail and provide one or two examples?

SM: I have done a number of murals where I worked primarily with youth from different neighborhoods, and then generated ideas based on my time spent with them and getting feedback from their neighbors and their community. Then usually I come up with the final design, which sometimes has areas where they can add their own individual touches.

The St. Jamestown mural I would say was very much a co-creation with the youth of St. Jamestown. The idea of the phoenix image came from conversations with the youth about the fire that burned through that building and displaced its residents. The youth wanted to have something very colorful to de-stigmatize the neighborhood and show that it is not just dirty and grey, that there is vibrancy and life, that there is more to the neighborhood than what people assume and to create a landmark for the community that they could be proud of.

In Lawrence Heights, a longer process of input and engagement with the community actually preceded the creation of the Ranee Avenue mural. You do not see this process in the final work, but it was a key part of the project. We did not spend the majority of time on painting or designing, but on running different workshops with the youth to learn about the neighborhood and its revitalization plan. We took them to community meetings because the youth were scared and did not know what was happening to their neighborhood. We spent a lot of time with the youth learning about the current state of the community and what they might want and need, and how this may be different from the major redevelopment plan. Based on these conversations, we realized that the community wanted and needed something positive.

For the mural designs on Ranee Avenue, which spread across four corners of an underpass, we started with a phrase from the community. They have a symbol, the “L”, that they show each other. It means “Love or Love.” Instead of “Love or Hate”, their only option is “Love or Love.” The design started with this phrase. From there, we added “Home,” and then “Limitless,” and “Heights”, a play on Lawrence Heights. It was great to see how quickly people embraced it. Soon after its completion, a TCHC scholarship for the community was created and called “Limitless Heights,” inspired by the mural. The following year, some of the same paint colors and phrases of the Ranee Avenue murals were used for another mural in the neighborhood. So, the work has taken on a life on its own, and this is really rewarding to see.

MF: What is your perspective on the role of public art for the city?

SM: I think art can play many different roles in the city. Public art can raise awareness and create dialogue and hopefully also create action around political issues. Much of our culture today is divided and people stay in their own echo chambers, they only hear the same opinions fed back to them and only seek out the same. For me, the role of public art is in starting a conversation where the issue is situated. For example, with many of our public spaces under threat of being privatized, public art can give people a sense of ownership of these spaces and encourage them to question private vs. public space. There are many ways to address this issue, and one way is to create art that encourages people to think and talk about it and take action in one way or another.

MF: In recent years a significant amount of new permanent public artwork in Toronto has been realized as part of private developments. How do you perceive the discourse around public art in the city?

SM: This is an interesting question. The nature of a permanent piece is different from something that is temporary or ephemeral. The permanent piece goes through a different process of creation. For artists applying for those permanent artworks it is difficult to take risks to push a conversation forward because it is not just you taking the risk. You have to convince the people selecting the artwork, and the artwork has to go through many levels of approval or bureaucracy before it can exist.

In recent years, I have observed a resurgence of attention toward art that is not pushing the conversation forward, there may be some new aesthetics or new formal aspects, but I see a lot of the same things over and over again. Back in the day, Henry Moore’s Archer sculpture was a revolutionary work for the pubic of Toronto. People were not ready for it. The Archer brought a public conversation out and it was really valuable for pushing the dialogue forward. However, abstract formal art has become normalized today; it is now often a safe choice, and it is chosen frequently. But on a critical or conceptual level, many formalist works are not pushing anything forward, and it could be argued that some of them take away space, opportunity, and funding that could be allotted to other forms of art. I would like to see a bit more risk-taking and more variety in the selection of permanent public artworks, but I recognize the constraints that are put on public artwork in the process, and the challenges to work with or around them.

MF: If there were not any constraints, what would be your dream project?

SM: This is a tricky one! I have so many ideas and projects I would love to do. And besides my art practice, I am also thinking about ways to create a more sustainable system and community to support more critical artwork, but that is a whole other topic!

The interview has been edited and condensed.

Melanie Fasche is a researcher and writer currently based in Toronto.

The Artful City is a Toronto-based collective that convenes discussions about the role of public art in Toronto through research and public engagement and creates space for more diverse and inclusive practices.