Last week a brilliant piece appeared in the New York Times about commercial advertising in public spaces and what the author describes as “the aggressive appropriations of the attentional commons“.

That got me thinking: I should probably write the next installment of this saga about aggressive appropriations of public space in Toronto. Here’s a quick summary so far:

Part I (June 2014): Surrounded by trees, two massive illuminated commercial billboards dominate a slice of green space, adjacent to a public park and a heritage site. Ten years ago, I asked city staff if the signs had proper permits. The answer was crystal clear: “We have researched these two signs and we have no records of any permits. …Our contractor is in the process of having the signs removed”. They were never removed.

Part II (July 2014): The City refuses to explain why the billboards are still there, using ‘confidentiality’ as an excuse which flies in the face of all the basic principles of any functioning democracy: transparency, accountability and access to information.

Here are two questions I asked in the prior posts, still unanswered:

1) How long should it take for a citizen in Toronto to determine if a commercial billboard is legal or illegal? (Ten years, and counting…)

2) Can City Hall protect our public spaces? Or are they powerless against the lawyers and consultants of the outdoor advertising industry which continues to use public space as their own playground, cluttering our scenery with visual garbage?

Here’s what I can tell you: Some helpful staff at City Hall’s Sign Unit are trying to sort out the situation. But it seems that the entire system is failing them, just as it failed me.

This is the most recent response I’ve received from :

“To put it simply, we are in a position where we do not know if there is a permit for the signs at 25 Burnside. As a result we cannot take any enforcement action on the signs at this time, however we will not be closing our investigation either. I appreciate that the answer “we don’t know” doesn’t give you a lot of satisfaction (it doesn’t give us much either!); however, it is what our position is for the time being.”

Legally, the onus is on the billboard company to provide evidence that there’s a permit and that clearly hasn’t happened. So it’s unclear why the city isn’t taking action against the company. As I wrote in the previous piece, I believe the most likely scenario is that the billboard company is threatening legal action, behind closed doors, and the City feels trapped. The only way out for City staff is to somehow prove that there is no permit. Which is kind of impossible. It’s been said that finding a needle in a haystack is a hard thing to do, but proving that a haystack doesn’t have a needle is much harder. But they’re trying anyway, and they’ve invited me along to help out.

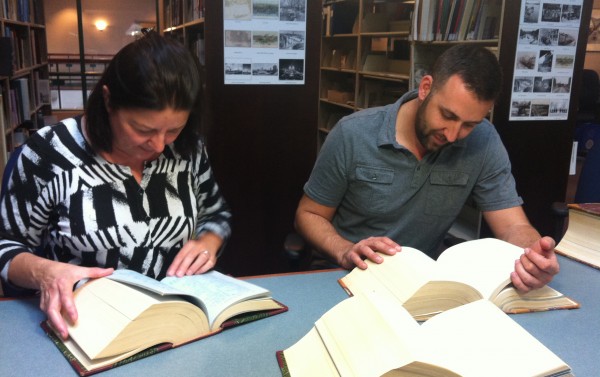

This is how it works: We go to the Toronto Archives, and we read through the minutes of City Council meetings. Really. I’m not joking. We’re actually going through a decade’s worth of public records, to prove that one particular item doesn’t exist. We’re not reading every word, of course. We’re relying on the indexes, looking up the street address, looking for any reference to the billboard company and looking closely at every single reference to any sign application in the city.

So far, we haven’t found a needle. But there is more hay to look through.

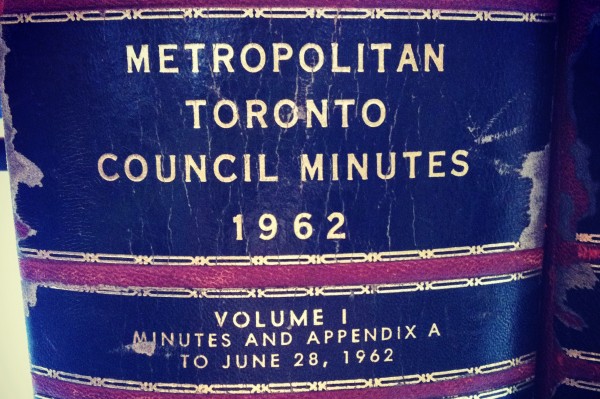

It gets a little complicated because these records are pre-amalgamation which means there are two sets of minutes for us to look at: The former City of Toronto and Metro Toronto. We’ve pretty much exhausted the Metro minutes, and we’re quite sure there’s no permit there. Every sign application for Metro is clearly indexed and clearly explained, and there is no reference anywhere for this sign. We know that these two signs were installed in 1963 or 1964, so we looked at records covering 1958 to 1965 – just to be safe. No needle was found.

But now it gets even more complicated. Metro was in charge of big roads, while the former municipalities like Toronto, Etobicoke, Scarborough, etc were responsible for the smaller residential roads. These two billboards are clearly on Bathurst Street, which means that the permit should have been given by Metro Council, not Toronto Council. Except the billboard company did a funny thing. Somehow, the property is legally registered as an address at 25 Burnside Drive, even though it doesn’t seem to touch Burnside at all.

No other piece of the forested hill is registered as part of Burnside, just the small slice with the billboards. And it’s unlikely that the property was originally surveyed as part of Burnside, since it’s entirely on a hill and not suitable for residential development. The address is also out of sequence with its neighbours. It’s as if the sign company had a special land severance created just for them, the exact size they needed, and with a street address that would get them under the radar of Metro.

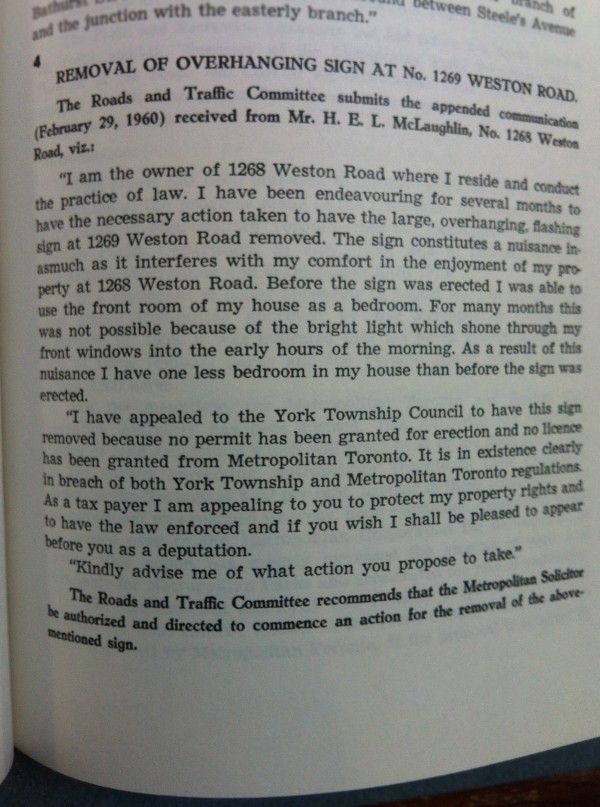

Perhaps, at the time, Toronto City Council was being more friendly to billboard companies than Metro was. Or, perhaps the City of Toronto wasn’t even paying attention to signs. There seems to have been a lot of debate back then about which jurisdiction should regulate signage, and there also seems to be a pattern that Metro was more strict with the outdoor advertising industry. Here’s an example, from the Metro minutes:

Metro Council was working in the public interest, by regulating signage and enforcing their rules. Was the City of Toronto? We’ll find out. I’ll be back at the archives soon, looking through more minutes from Toronto City Council meetings trying to find something that I’m quite sure doesn’t exist.

The task is enormous. Remember the final scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark?

A few years ago, I was coordinating a team of volunteers who were researching the history of Toronto’s Bureau of Municipal research, and I made this Raiders-themed video as a tribute to the Archives:

I love the Archives. I think it’s one of Toronto’s greatest treasures. But something is deeply wrong with our democracy, when someone has to go to the Archives to prove that a particular paragraph isn’t on the shelves. To find an Ark that was never placed there.

In the meantime, the commercial billboards are still standing on Bathurst Street and Outfront Media continues to profit daily from their ‘aggressive appropriation of the attentional commons’.

NEXT: Part Four

14 comments

I have one simple question for the City: why is the burden of proof is not on a sign owner to demonstrate that they have a permit? The default position should be that all signs are illegal unless they have proof of a permit. If someone is doing major construction or renovation on their home, they have to display a building permit. If a restaurant or bar serves alcohol, they have to have/display a permit from the LCBO. If I purchase time for street parking, I have to display my proof of payment for that, or I’m towed.

Why is this different?

What a bizarre situation! I’m with Mark–it seems ludicrous that it isn’t the company’s responsibility to prove it has a permit. Seems it would be sensible to require that billboards have copies of their permits affixed somewhere on the billboard itself. And by the way, if the company does have a permit, shouldn’t it also be paying, at least annually, to renew the permit for the privilege of profiting from the attention offered by public space?

Something is rotten in Denmark. Otherwise just remove them.

Would it be useful to digitize these minutes? I can’t imagine a good reason why they couldn’t be bulk scanned and ocr’d so that they could be searched easily. Just as a historical resource this would be useful.

Aren’t there fees associated with permits?

I know financial records tend to have a seven year retention. However, you would think that permits such as these would be renewable (annually to every five years) and that the advertisers should have to pay the City for such privileges. And, if there was no record of permit, at least there would be a record of payment. Time to revisit and review.

Re Mark Kuznicki:

I disagree, these signs have been up for decades, the company has invested (and, yes, profited) quite a bit of money into their presence, and no one has minded.

It would be one thing if the signs were in the process of being erected (“where is your permit?”) Or were recently erected (“did you have a permit”) But more than 50 years have gone by! Some things should just be grandfathered in, because, yes, records get lost, and corporate archives are as a rule not very well organized.

I would be very upset if the city came to me and asked me to prove that work done at my house 50 years ago (by someone else entirely) was done with a license and permit. And I’d feel reasonably confident going to a judge if I was asked to take down said work that the request was simply unjust, and unfairly putting me out of pocket.

It’s entirely reasonable for the private company to insist that the city make its case instead of randomly imposing costs (and depriving wealth) from a property owner because a cranky private citizen is upset. Should I be able to have the Royal York hotel torn down because it didn’t have a permit to be built as high as it was in the 1920s? Can the current owners prove they had a permit to build it that high? No? Tear it down!

(Sorry Dave. I’m enjoying the saga… I just disagree with your sense of entitlement on this one. But good on you for putting the work in.)

-R.

Ever since the Catholic Church started selling indulgences many centuries ago, the rich have believed that – if they have the money – they can damage whatever public good they wish to damage. “God said.”

Arguing against Money (job-creators) is like arguing against the Creator Himself. The public (faithful) are only entitled to the peace of mind that they can afford to buy back from rich polluters.

/Entitlement

Hey Richard!

Three differences between billboards and hotels:

1) There is no chance that the Royal York was built without a permit. It’s a REALLY BIG building, and Toronto has always enforced strict building codes for large structures. Billboard companies, on the other hand, have a long history of ignoring bylaws and putting up signs wherever they want. The histories are very different.

2) Building permits last forever. Sign permits do not. When you build a hotel, it’s understood by all parties that the building will be allowed to stay in it’s place in perpetuity. Toronto’s current sign bylaw, however, only grants a five year (5? I think it’s five…) permit that must be re-submitted at the end of the term. In other words, the sign companies have to consider their investment in the context of a short-term business plan. There is no guarantee of renewal… unlike the Royal York which will stand forever as long as the structure is safe.

3) People like hotels. This is not a subjective thing, it’s just a true fact. People like hotels and don’t mind having them in their cities. While cities across the world are banning billboards (Sao Paulo, Grenoble, Montreal’s Plateau Borough and the entire states of Vermont, Maine, Alaska and Hawaii), I’ve never heard of a city that has banned hotels. Truth is, most people find billboards annoying, and hotels convenient. Our government’s job is to help us, as a society, collectively aspire to surround ourselves with things that we like, and regulate and remove the things that we don’t like.

Hi Dave,

Point 1) Agreed. I raised it as a point of illustrative hyperbole. Let’s suppose the Royal York overshot its approved building height by 5 storeys. We wouldn’t be able to do anything about it now.

Point 2) Building code changes, when updated, allow for grandfathering for buildings/structures already permitted. I imagine the same is true for signs, and, based off the property quirk you’ve found, it looks like the sign-erector, put the effort in at the time to get permission… however weaselly a way they went about it aside (Though, I am curious to see what you find at the end of this research–and the land registry may make it much easier to find out when the lot was severed to create the property they are on, helping you narrow down the timing.) I don’t think a judge would let you suspend all permits and licenses for billboards on the basis of “now they need 5 year renewals.”

3) As I said, the hotel example was hyperbole. Your presented thesis is one interpretation of what government’s job is. We have elections and debates and open government because not everyone agrees with you on that. Consider questions like “how should drinking be regulated?” through the lens you’ve proposed, and you can come up with a very unpopular answer. The presence of billboards helps some people pay the rent/mortgage… and much like low-rent housing in a gentryifying neighbourhood, it shouldn’t be taken away from the current beneficiaries by the government just because suddenly a citizen with time/influence/an axe to grind decides they don’t like it.

But thanks for writing back… and do keep up the good fight. I may not agree with what you say, but I admire your doggedness in pursuing it.

To George Bell –

There’s one obvious reason the Archives doesn’t just scan all their documents. It requires resources like time, equipment and staff. Those resources cost money and clearly, this is not a priority for the city to be allocating funds towards.

There are also tech issues to consider in terms of long term storage and surprisingly, hard copies of paper still tend to be the most stable medium.

That said, the Toronto Archives has made a lot of progress in scanning documents and especially images to be made available to the public. Check out their twitter feed, it’s great.

Hi Dave, I applaud your efforts but just wanted to caution you about investing too much time, or hope, on any historic permits, or bylaws.

I have gone down that road. It took two years to figure that out!

When I was researching some land history for a cause I discovered land that had been given to the people as a park with a bylaw – never rescinded, then sold to a developer, a building built too tall for its permit, minor fines, now precedent for height and on and on.

Did you know that bylaws need not be enforced? Hence no need to rescind.

All that will matter is what direction the City is being pressured to act in now. Everyone just wants to keep their job might be a thought you keep top of mind. Lots of nice folks with their hands tied by their mortgages. Follow the money, honey…

Why not talk to the brands that advertise on the billboard?

This is unbelievable. If the city isn’t willing to enforce in a situation like this, I doubt they’ll ever take a single illegal billboard down, since there would always be *some* uncertainty about whether a permit may have been issued eons ago.

The onus should be on the recipient of a permit to prove its existence. This is reflected in section 25(9) of the Provincial Offences Act (and this would be a prosecution under that act), which provides that the prosecution does *not* need to set out that the defendant is not entitled to an exception in the law (e.g., a permit). Just as common sense dictates, it’s up to a defendant to prove it is entitled to the benefit of an exception in the law.

– A Provincial Prosecutor

A billboard should have to licensed and a “plate” attached to each billboard with a serial number that can be traced and must be renewed annually just like a motor vehicle, taxicab, etc. A billboard is a “business” and most businesses in Toronto (and elsewhere) require a municipal license and it must be displayed.