Humans are a resilient species. We have reached nearly every corner of the globe and adapted our lifestyles over generations. However, the high concentration of people in cities and growing threats of climate and social crises is increasing the vulnerability of our populations at an unprecedented scale. In response, national governments and international organizations are introducing resilience strategies. Resilience is “the capacity of social ecological systems to absorb shocks, utilize them, reorganize and continue to develop” (Colding et al., p. 95). In winter 2018, Infrastructure Canada put forward a Smart Cities Challenge that will award winning communities up to $50 million to implement Smart Technology in their communities. The City of Vancouver partnered with the City of Surrey to prepare its Smart Cities application. What role could smart technology play in building our urban resilience?

The Smart City is characterized by ubiquitous technological monitoring and regulation networks. It aims to improve the flow of goods, people, and information, and is often presented as the solution to all urban challenges. As cities become “smarter” by adapting to our lifestyles, the technologies also shape how residents live. “Technology, as a key form of cultural adaptation, has had and does have the ability to alter profoundly the trajectory of our evolutionary path” (Fox et al., p. 202). In short, Smart City technology is shaping the future of the human species: how do we want to evolve?

Smart Cities and Disaster Management

Currently, Smart City innovation and applications are overwhelmingly introduced by top-down governmental processes. A report by the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSMA), highlights the importance of secure Information Communication Technology (ICT) networks, Big Data and centralized planning for disaster monitoring and response. Japan launched a large-scale emergency notification system in 2007, which prevented significant loss of life and damage from the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. ShakeAlarm, which was first installed in a Portland building in 2015, can detect the P-waves of an earthquake, which are the lower energy fast waves that precede destructive S-waves. It alerts residents, shuts down gas and electricity, and activates an alternative power source.

According to the UK Technology Strategy Board, global private investment in such technologies are estimated to surpass $300 billion by 2030, and can lead to valuable initiatives: following Hurricane Sandy in 2012, AT&T provided charging stations and roaming coverage in New York City. However, municipal governments become increasingly influenced by the technological push of corporate entities, rather than the demand-pull of citizens. Residents become “users, testers or consumers” (Capdevila & Zarlenga, p. 267) and risk losing their power in shaping the city. The city of Christchurch, New Zealand received an IBM Smarter Cities grant following its destructive 2010-2011 earthquakes, which led to the formation of a non-profit organization called the Sensing City Trust. However, the trust dissolved. Christchurch residents were more interested in rebuilding their community through citizen-driven initiatives than investing in long-term technological advancement (Marek, Campbell, & Bui).

Another challenge for Smart Cities is that the more interconnected a system is, the more vulnerable it becomes. Smart Cities coordinate data flow between previously isolated systems, which increases their vulnerability: “there are vast problems related to hacking, sabotage, and terrorism that could cause collapse of large-scale critical infrastructure, like electricity, ICT, and hospitals” (Colding et al., p. 97). There is no denying that top-down smart disaster response infrastructure can quickly generate and contribute a significant amount of important data for disaster planning and response. However, the possibility of error and vulnerability is undeniable. For this reason, implementing smart technology also requires fostering resilient people.

Social Resilience

According to Boon, a community’s ability to effectively bounce back depends on efforts to improve social cohesion and create networks. City-dwellers evolve within the systems they inhabit and will respond to ecological events accordingly. In his book called The Shallows, Carr explains that tools shape the connections in human brains: as repeated actions and thoughts turns into habits, they become the default neurological pathways. If a Smart City uses sensors to constantly monitor and regulate the urban environment, the residents are no longer required to adapt to minor changes in their surroundings. Will humans still be able to survive environmental crises without technology? By losing our ability to adapt to change and deal with uncertainty, I fear that we risk neglecting our social resilience in favour of technological solutions.

The case of Christchurch demonstrates a tension between top-down data-driven decision-making and democratic, citizen-led data collection that are both embedded in the Smart City concept. Marek et al. argue that the most successful Smart projects will be those that include and empower the local community members. Barcelona has become a leader among Smart Cities that integrates open data initiatives, sustainable city growth initiatives, and alliances between private and public institutions (Capdevila & Zarlenga).

The Neighbour Hub

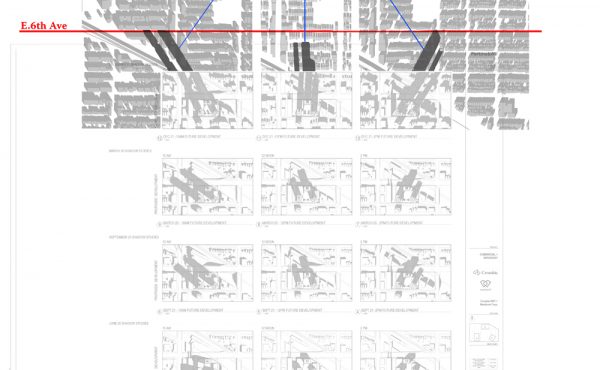

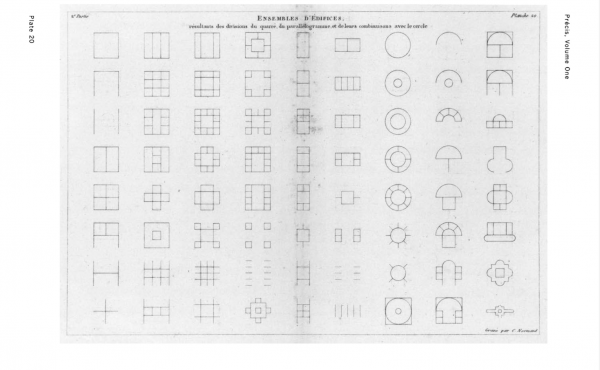

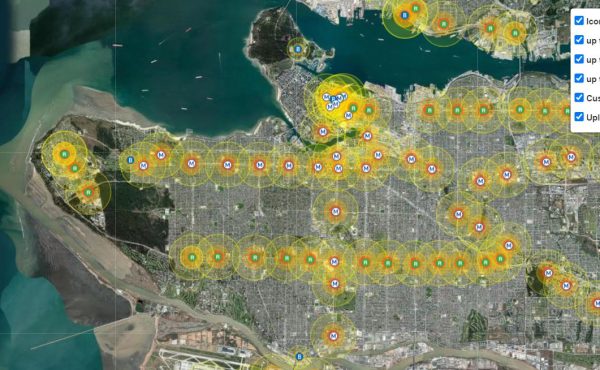

Since October 2017, I have been working with a team of designers, geographers and urban planning students on a Smart Technology design that builds social resilience: Neighbour Hub. It is a structure to be implemented in public parks that responds to the implications of a crisis by offering energy, water, and communications—all independent of the city’s existing power and water supply. Neighbour Hub builds social resilience by engaging community members in its design and stewardship, and by sparking conversations in the neighbourhood around disaster preparedness. We are now working with the City of Vancouver’s Resilience Team to build a full-scale prototype by Fall 2018. Through our iterative process, we are building knowledge, identifying community assets, and creating connections that (we hope) will create not only smart technology, but stronger communities.

As our cities embark on “Smart City Challenges” and compete for global recognition for their state-of-the-art technology, it is important to keep our priorities straight. The appeal of smart technology as a tool for building resilience is often misinterpreted as a replacement for other crucial tools, such as strong social cohesion, local contextual knowledge and experiential learning. For this reason, it is important that we develop tools and spaces to encourage citizens’ abilities to creatively adapt to our environment, particularly in the face of an uncertain future.

**

Adele Therias is the Engagement Coordinator for Neighbour Lab, a multidisciplinary design and urban planning studio that aims to develop neighbourhood-level resilience through civic engagement and collaborative design. She is currently completing her B.A. in Geography at the University of British Columbia.