Anybody who has experienced a well-used public transit system during rush hour knows that relaxing their ‘personal space bubbles’ to a minimum is necessary. It’s certainly not for the agoraphobic, with bodies smushed in all types of twisted configurations based on grab bar availability and seat arrangement.

City subways and buses are the mainstays of the public transit system and although localized differences characterize transit system design around the world, similar to the corridor and dimensions governing the classroom, they are largely subject to international standards. Interestingly, despite differences in speed and form buses and subways dimensionally fall within very similar and narrow width margins. To understand why requires a little historical context.

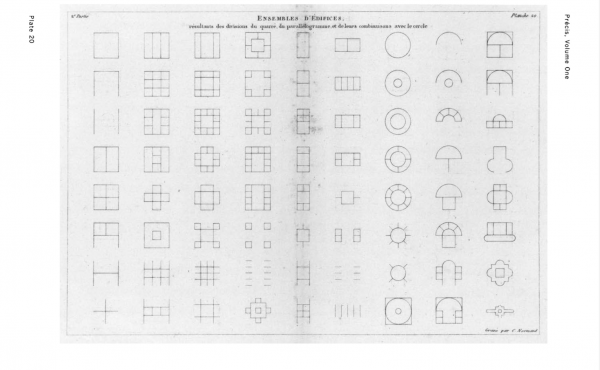

What makes public transit unique compared to the corridor and classroom covered previously, is that the origins of the dimensions governing public transit are connected to a larger system of measures governing street widths and traffic lanes. These, in turn, are connected to the human body, but in a less direct way than corridor widths and furniture arrangement measures.

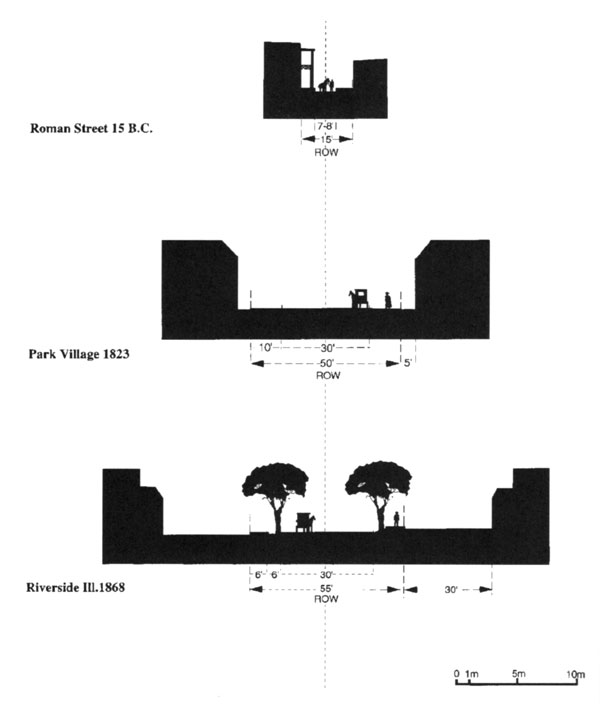

The earliest known law regarding street width dates back to about 100 B.C.E. and was written by the history’s greatest pre-modern road-builders—the Romans—who prescribed a minimum street width of 15 feet (4.5 m). Anyone who has traveled to one of the many Roman-founded settlements around the world will know that street widths vary—from anywhere between 8ft-40ft (2.4m-12.2m)—but on average, main Roman roads ranged between 12ft-24ft (3.7m-7.3m).

It’s important to note that the width dimensions are what would, in modern terms, be called the ‘right-of-way’. That is, they refer to the total width between buildings, a space that was further subdivided into zones for walking, vehicles, etc. As one can see from the cross-section of a minimum Roman side road below, the space allocated to the street itself—the ‘traffic lane’ if you will—was roughly 7’8” (2.4m).

Where this dimension came from is unrecorded, but if the rules governing early Arab-Islamic settlements are any indication, street widths were based on a combination of human and animal body dimensions. For example, the minimum widths for through-traffic, by-directional routes within Arab-Islamic cities were governed by people riding two packed camels side-by-side (roughly 10ft or 3.2m).

Although street rights-of-way have varied over time—exploding to huge widths over the past 200 hundred years to include sidewalks, boulevards and multiple lanes—lane widths remain largely the same, currently sitting on average between 10ft-12ft (3m-3.6m). This matters because modern vehicles conform to this standard, a few steps removed from—but related to—the body.

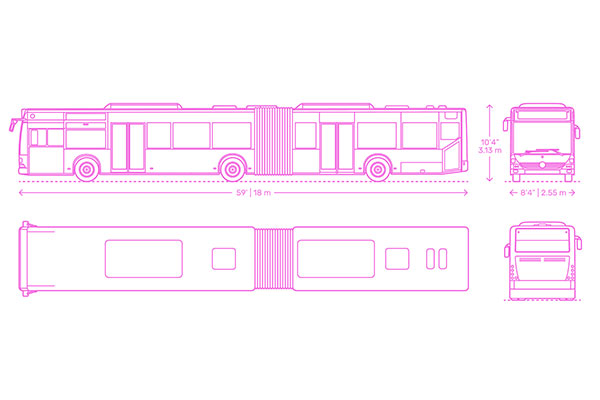

Thus, bound by standard traffic lane dimension, buses typically have exterior measures of 8.5ft (2.6m) wide, not including the side-view mirrors. This is similar to standard subway cars that have tunnels whose diameter is similar to traffic lane widths. Metro Vancouver’s Skytrain Expo-Millenium Line cars sit at 8.7ft (2.65m) width, for example, while Canada Line cars are a spacious 10 ft (3m).

In the Six-Foot City, riders could only be accommodated along the perimeter edges of public transit vehicles, with no circulation along its centre. Current vehicles would effectively have to be completely redesigned. Limited by lane and tunnel widths, however, vehicles would necessarily have to expand in length to accommodate riders. This longitudinal expansion would be significant in places that have high ridership. Buses would become longer, taking up much more street space, with potential implications for traffic congestion.

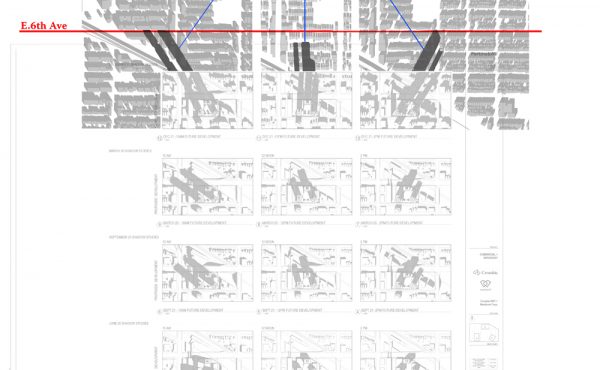

Along heavily used roads, one can imagine buses being replaced by light rail systems for ease of driving, ultimately creating extensive region-wide light rail networks. Public transit systems that wanted to maintain the vehicle designs would need to expand their fleets extensively in order to accommodate fewer users per vehicle.

The short-term capital costs associated with transforming an entire fleet of public transit vehicles to accommodate the requirements of the Six-Foot City would be astronomical. This would have to be accompanied by larger systemic infrastructural changes, such as expanding train platforms so that riders can board the longer trains. Fuel costs associated with moving more and/or heavier vehicles would necessarily increase but not with an increase in ridership. This would change the economic structure of public transportation networks, potentially leading to increased fares and, therefore, decreased ridership.

This might spur an explosion of alternative, more cost-effective movement options. This could be in the form of low-impact ‘sustainable’ solutions, like bicycles and scooters. Equally likely, however, is the increased use of cars and all the environmental implications that this brings.

This brief journey into public transit in the Six-Foot City demonstrates the complex system of urban movement systems and how much we take for granted riding buses and subways every day. It’s hard to imagine the connection between a person riding a packed camel and the capacity of a bus, after all. As such, it serves well to show the layered complexity of our built environment and the hidden role bodily dimensions play within it.

***

You can read the other pieces in the Six-Foot City series here:

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements across Scale and Culture. He is also an educator, independent researcher and designer with personal and professional interests in the urban landscapes. His private practice – Metis Design|Build – is an innovative practice dedicated to a collaborative and ecologically responsible approach to the design and construction of places. You can see more of his artwork on his Visual Thoughts Tumblr and follow him on his instagram account: @e_vill1.