By John Lorinc and Alex Steep

At a raucous public meeting about the future of Bickford Park last year, emotions ran high. Some residents wanted to remove one of the park’s two baseball diamonds to make space for other activities in the increasingly sought-after space, including a dog run.

Others objected, and did so in no uncertain terms. “I can’t believe you are trying to take baseball away from little kids!” Mike Zimmerman, a baseball league organizer bellowed at Councillor Mike Layton, who was presiding.

In an ideal world, the city would simply create more parks for a growing community whose residents live in small homes or apartments with no backyards. But, as Layton said later, “There is no more space.”

Or at least, not unless the City is prepared to expropriate land, which is unlikely.

The showdown over the future of Bickford Park has become an ever more common narrative in much of the city’s core. Residents in high-density neighbourhoods — especially those in areas that have seen rapid intensification due to the condo boom —have been forced to battle each other over what little space they have, setting up a corrosive dynamic that pits neighbours against one another and shortchanges future residents.

The demographics tell the tale. Between 2001 and 2012, Toronto’s population jumped by more than 10%, or 226,000 residents, to 2.7 million – a trajectory that puts the city well ahead of growth projections set down as part of the official plan in the early 2000s. At the time, planners figured the City would add 540,000 people in 30 years. In just over a decade, however, we’re now 41% of the way to hitting that target.

Much of that growth has been concentrated in high development precincts, like the Bay Street corridor, King West and Liberty Village, which saw its population leap by 143% between 2006 and 2011, according to census figures. (The overall population of Niagara, which encompasses both Liberty and King West, grew 83% between 2001 and 2011.)

The City likes to boast about its open spaces, citing how its 1,600 parks and 600 km of trails encompasses 8,000 ha, or 13% of Toronto’s area. As every park entrance sign duly notes, Toronto is “a city within a park.”

Yet it’s become apparent that there simply aren’t enough parks within the city, or at least certain parts of the city. In areas of high growth, and the dense older neighbourhoods that abut them, the City of Toronto has largely failed to create new networks of parks and substantial public open spaces sufficient to accommodate the needs of tens of thousands of new apartment dwellers.

The 1.1 ha of park space in the middle of Liberty Village is almost comically inadequate for an area with an estimated 6,000 residents and thousands more day-time office workers. The City, meanwhile, has neglected to properly maintain the 3.1 ha Canoe Landing Park on the City Place lands. David Pecaut Square and College Park have limped along for years with no improvements, despite increasing density all around both and calls for revitalization from residents and local landowners. And there appears to be no money, or political will, to transform marginal spaces – e.g., the string of parkettes known as The Green Line that run along the midtown Toronto hydro corridor or extensions to the West Toronto Railpath – into viable parks and trails.

WHAT OUR INVESTIGATION WILL REVEAL

As Spacing will show over the coming week, the problem is not one of a lack of resources. As of September, 2013, the City had $217,013,695 in its Parkland Acquisitions & Development Reserve Fund, a little more than half of which is earmarked to obtain new parkland according to a formula established by council shortly after amalgamation. That number has grown in the past two years, with $248 million sitting in those reserve funds as of September, 2014. (According to the latest capital plan, the balance in those reserves will drop to $221 million by 2017 because of spending on new projects, including $23.5 million on new parks and park improvements in South District, which takes in the former City of Toronto and parts of York and East York.)

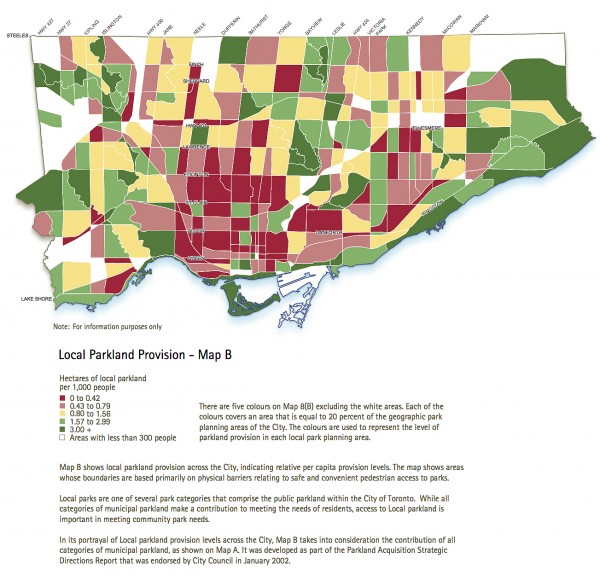

Council maintains the fund to keep the provision of park space in line with development and population growth — or at least that’s what the Official Plan says. As a 2001 staff report noted by way of explanation, “The amount of projected growth will, unless accompanied by parkland acquisition, tend to reduce existing per capita parkland provision levels. This is a particular concern in areas of the City that currently experience low levels of parkland provision.” In other words, the denser the city becomes, the shortage of public open space in some areas becomes ever more acute.

According to the Toronto Parkland Acquisitions Strategy, developers may either set aside a portion of their property as a public space, or pay cash-in-lieu, on the understanding that the City will acquire parkland or open space at some future date. The overall goal, as that 2001 report stated, was “ensuring that adequate levels and types of parkland are planned and built into new and transforming communities.”

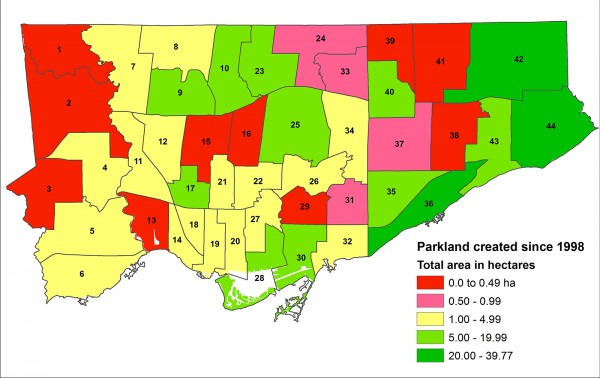

The top map, which is from the 2002 Official Plan, shows parkland provision levels across Toronto. The lower map, based on data provided by the City*, shows parkland created since 1999, by ward. Download the OP and data files

In the last four years, according to information obtained through access to information requests, developers have handed over vast sums for parkland acquisition and improvement. Much of that money remains unspent, although city officials stress there are projects in the pipeline, including a new downtown park at 11 Wellesley Street. However, when city parks officials do negotiate an acquisition, they are far more likely to acquire land in suburban neighbourhoods, where property is inexpensive, than in fast-growing downtown communities, where real estate prices have shot through the roof.

There’s something deeply wrong with this picture, and the policy drift that’s taken hold in recent years raises tough questions: Why can’t the city secure land in areas seeing a sharp uptick in the ranks of apartment dwellers if there’s money earmarked specifically for that purpose? Why have city officials stopped pushing developers to dedicate land instead of offering a cash-in-lieu payment, despite planning goals that clearly specify the importance of creating more open space to accommodate growth? Last, what are the long-term consequences for Toronto if municipal officials and our elected politicians fail to reform a system that, by almost all accounts, is badly broken?

* The parkland creation data provided to Spacing by the City may not be complete.

Part 1: All built up but no place to grow

Part 2: Where the money flows

Part 3: The perils of cash-in-lieu

Part 3 sidebar: Section 42 explained

Part 4: The tale of two parks

Part 5: The system worked (slowly) for a west end park

Part 6: Are privately-owned public spaces the answer to parks deficit?

top photo by Wylie Poon; middle photo by Kenny Louie; lower map by Sean Marshall