Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from Reinier de Graaf’s recently published book, Architect, Verb.: The New Language of Building, critically analyzing Vancouver within the context of its claims of ‘liveability’. A heartfelt thank you to Reinier de Graaf and Tim Thomas at Verso for collaborating so well to make this possible.

Guest Author: Reinier de Graaf

Since 1998, global human resources consulting firm Mercer has been publishing an annual list of the most liveable cities in the world. It does so by assessing the living conditions of more than 450 cities worldwide, 231 of which make it to the actual list. The list aims to provide internationally operating companies with a basis upon which to establish hardship allowances for employees sent on assignments abroad.

The evaluation happens along a fixed set of criteria—thirty- nine to be precise, grouped into ten categories: 1) the political and social environment, assessing factors such as political stability, crime and law enforcement; 2) medical and health considerations, looking at medical supplies and services, the prevalence of infectious diseases, potable water, air pollution and the presence of dangerous animals or insects; 3) public services and transportation, listing electricity, water, public transportation and traffic congestion; 4) consumer goods, considering the availability of food and daily consumption items; 5) recreation, looking at the availability of restaurants, theatres, cinemas, sports and leisure facilities; 6) the sociocultural environment, weighing (media) censorship and limitations on personal freedom; 7) the natural environment, focusing on the city’s record of natural disasters; 8) housing, assessing the standard and cost of (rental) accommodation, household appliances, furniture, and maintenance and repair services; 9) the economic environment, considering currency exchange regulations and banking services; 10) education, focusing on the availability of international schools.

Each of the thirty-nine criteria receives marks on a scale of 0 to 10. The average of the marks within each group of criteria determines the eventual mark for each of the ten categories. Marks per category are then weighted according to perceived importance. Not all categories weigh equally. The further a category is down the list, the lower its share in the weighted average between categories. The top four: the political environment, health considerations, public services and the availability of consumer goods account for respectively 23.5, 19, 13 and 10.7 per cent—two-thirds of the overall scoring—while the remaining categories each contribute less than 10 per cent.

Depending on their overall score, cities emerge as ‘ideal’ (80–100 per cent), ‘acceptable’ (70–80 per cent), ‘tolerable’ (60–70 per cent), ‘uncomfortable’ (50–60 per cent), ‘undesirable’ (less than 50 per cent) or ‘intolerable’ (no percentage given), which is further explained as there being ‘few’, ‘some’, ‘certain’, ‘substantial’, ‘extensive’ or ‘insurmountable’ challenges to liveability.

Mercer’s Quality of Living Survey is one of three major city liveability rankings. The others are the annual Global Liveability Index by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), The Economist’s research and analysis division, published since 1999, and the ‘most liveable cities index’ by lifestyle magazine and media brand Monocle, published since 2008.

[….]

Despite the differences in measuring methods, the lists tend to feature the same cities. In 2019, Vienna topped not only Mercer’s rankings but also the EIU’s index, while it occupied a comfortable fourth place on Monocle’s top ten; Zurich, the number two on Mercer’s list, featured first on Monocle’s; Copenhagen featured on all three lists; Munich featured on two out of three, as did Vancouver and Melbourne. Such homogeneity may have a lot to do with the sources upon which they relied: ‘in-house experts’ in the case of the EIU, ‘correspondents’ in the case of Monocle and expatriates already living in the reviewed cities in the case of Mercer.3 In all three cases the ‘objective’ data concern the subjective opinions of individuals. Mercer even relies on the opinions of those who chose their city based on Mercer’s prior lists. The mechanism which ensues is predictable: Favourable reviews attract more expats; more expats generate more favourable reviews, and each list becomes input for the next. Last year’s liveability rankings barely differed from those of the previous year, or the year before that.

Liveable, livable, vital

The term ‘live-able’ was first recorded around 1610, in England, where towns suffered severe outbreaks of the bubonic plague. It was used in the now-obsolete sense of ‘likely to survive’ and generally had to be accompanied by the prefix ‘un’. The first time the word ‘liveable’ occurred in modern literature was in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park, used in relation to the proposed modification of a country estate: ‘There will be work for five summers at least before the place is liveable.’ No longer does the term relate to the possibility of life itself; it is now applied to the habitat in which we live and the possibility of its constant improvement.

The term entered discourse on the city with Lewis Mumford’s essay ‘Restored Circulation, Renewed Life’, published in 1956: ‘If the city is to become livable again, and if its traffic is to be reduced to dimensions that can be handled, the city will have to bring all of its powers to bear upon the problem of creating a new metropolitan pattern.’

Like Austen, Mumford applies the term to the human habitat. The word ‘again’, however, signifies an important difference. With Mumford, ‘livable’ is a condition presumed to have once existed but is now lost—the cause of which, he leaves little doubt, is attributable to rampant modernization and mass ownership of the automobile which has deformed cities beyond recognition. No longer is the term ‘liveable’ weighed against the forces of nature and decay; it is the technologies unleashed by humanity itself which must be mitigated.

The same polemic also underlies Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which appeared five years later. Where Mumford used the term ‘livable’, Jacobs speaks of ‘urban vitality’, defined as ‘something that the plans of planners alone, and the designs of designers alone, can never achieve’.

Jacobs’s mistrust of the powers of planning owes much to her own personal history as a resident of Greenwich Village—a neighbourhood subject to plans for a large overhaul by then-New York City planning commissioner Robert Moses.

[….]

Maoists, Communists, pinkos, left- wingers and hamburgers

Such controversies prevailed in many North American cities at the time. But it was not New York City or Toronto but Vancouver in which Jacobs’s views—which until then had taken the form of protesting pending developments—first resulted in a propositional alternative.

By the early 1960s, Vancouver had grown into Canada’s third-largest city. In the decade before, it had witnessed a sprawl of suburban development and massive increase in car use. To cope with the city’s increasing transportation problems, the ruling Non-Partisan Association (NPA), which had been governing the city since 1932, had created the Technical Committee for Metropolitan Planning in 1954, which, together with several neighbouring municipalities and the provincial government, had submitted the so-called Freeways with Rapid Transit report in 1959: a US$450 million master plan for freeway construction across the Vancouver region.

However, with no central authority responsible for working

on the city’s freeways—decision-making was divided between the federal, provincial and civic governments—the city council was left on its own to raise funds for the freeways. Hoping to secure funding from the federal government, which was charged with building the Trans-Canada Highway, the city prioritized the construction of a freeway that would connect the downtown with the highway. Incidentally, the freeway would cross Chinatown and Gastown, two neighbourhoods that qualified for urban renewal funding from the provincial and federal governments.

Rather than solving traffic problems, the approach caused political turmoil. Leading figures in the city began to speak out against the proposal. At the University of British Columbia, an array of guest lecturers highlighted the negative impact of freeways on cities, essentially turning Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities into a manifesto of popular resistance against the plan. The idea of a freeway across Vancouver’s Chinatown also met with opposition from the business community.

[….]

In the spring of 1967, in a meeting at the headquarters of the Chinese Benevolent Association, a broad coalition against the city council was formed. When, despite promises to re-evaluate the freeway’s planned route, the city decided to press ahead regardless, protests broke out. A march took place through the neighbourhood, participants dressed in black for the occasion. The protests were supported by the city’s upper-income groups, too. A stinging article in the Vancouver Sun protested vehemently against the city council’s plans, raising the argument of lost liveability: ‘The democratic process has been thwarted… by people who are planning a city the majority of citizens don’t want to live in.’

In the North America of the late 1960s, protests to new freeway plans were by no means a rarity. In the US alone, at least twenty-six cities experienced such protests, including New York, Boston, Chicago and San Francisco.

[….]

Encouraged perhaps by the success of those protests, opposition against Vancouver’s freeway plan persisted and the first results seemed to manifest in the fall of 1967, as the federal government announced that it would no longer contribute to Vancouver’s freeway through Chinatown. Following the announcement, support within city council for the plans began to wane.

[….]

Later that year, the Great Freeway Debate ended with Vancouver’s City Planning Commission chairman resigning, leaving the plan to be scrapped in January of the next year.

A freeway construction programme remained on the political agenda, however. But with city hall unable to muster either the cash or a political majority to execute such a programme, responsibility was transferred to the federal and provincial governments, with most of the money coming from Ottawa. Initially hesitant to adopt the new plans given the previous experience, the city council accepted the proposal in 1969. New protests erupted and the city was eventually forced to suspend its decision. Asked for a reaction, then-mayor Tom Campbell blamed ‘Maoists, Communists, pinkos, left-wingers and hamburgers for having sabotaged the plans. Notwithstanding his feisty rhetoric, the federal government formally struck down provincial commitment to the project in 1972.

The Electors’ Action Movement

The success of the protests put an end to forty years of uninterrupted rule of the NPA. In 1967, on the heels of the Great Freeway Debate, a new local political party formed: The Electors’ Action Movement, operating under the acronym TEAM. TEAM had been the initiative of two key players in the freeway protests: University of British Columbia geography professor Walter Hardwick and Art Phillips, head of a successful Vancouver investment firm. Their liaison—a joining of academic and business forces—produced a centre-left political party which aimed to appeal to persons of all political ideologies. NPA’s handling of the freeway crisis had helped profile TEAM as the progressive, more community-oriented alternative.

[….]

In the municipal elections of 1972, TEAM won a majority on the city council and Phillips was elected mayor of Vancouver. Once in power, TEAM made some radical changes. No longer was city-owned property sold off to private parties, using the proceeds to keep taxes low. Instead, Phillips created the property endowment fund, where all revenue from the city’s extensive holdings was deposited, invested and used for the benefit of the city. This paved the way for a much greater role of the city in its physical planning. For the inner city, a new planning policy was introduced with a focus on mixed land use, social diversity, environmental awareness and public housing. Freeways and high-rise buildings were out; neighbourhood planning was in.

A first opportunity to implement those policies presented itself in the form of the redevelopment of the industrial lands on the south shore of the False Creek inlet, directly adjacent to Vancouver’s downtown. With a freeway crossing no longer on the cards, the TEAM-dominated council saw the opportunity to transform the area, previously assigned for industrial use, into a showcase of their new urban planning policies. Under federal funding a master plan was developed for a mix of one third each of non-market rental housing, co-ops and condominiums. Social interaction between residents was promoted via the introduction of ample outdoor public space (including the public use of the waterfront) and indoor public facilities such as the False Creek Community Centre. Several renowned local architecture firms were involved in the design of the individual buildings, which, through a gradual increase in height of the buildings—from three- or four-storey townhouses near the water to eight-to-twelve-storey buildings further away— maintained mountain views for all residents, irrespective of tenure. To add further credibility to the new development, Mayor Phillips and his family moved to a condo in the fledgling neighbourhood themselves.

After Phillips left office in 1976, False Creek South became the calling card of Vancouver’s new urban planning policies. Until Phillips’s tenure, the default growth model for North American cities had been the creation of suburbs, connected to a monofunctional downtown area via an ever-expanding freeway network. False Creek proved that cities could also grow inward. As a mixed-use, mixed-income neighbourhood designed by multiple architects, geared towards pedestrians and achieving a high density without a single high-rise building, False Creek was the place where the ideas of Jane Jacobs, the woman who had inspired the protests, acquired physical form: a built critique of the failed urban renewal policies of the 1950s or, in the words of Art Phillips: ‘A place which brought people in, not threw them out, making the city a place to enjoy, where people wanted to live.’

The liveable region 1976/1986

The political shift which had taken place in Vancouver in the early 1970s was mirrored by a similar shift on a provincial level. In 1972, British Columbia had taken a significant step to the left with the election of its New Democrat provincial government. The presence of like-minded governments at the municipal and provincial levels created significant momentum for the revision of planning policies, not just in the city of Vancouver, but across the entire region.

From just over half a million inhabitants in the mid-1950s, the Vancouver region was expected to grow to about 1.5 million by the mid-1980s. Sandwiched between the mountains and the water, the region’s natural setting, the land available for new developments was limited—a situation which was exacerbated by British Columbia’s policy of protecting agricultural lands. Since 1968, local governments had been informally collaborating under the umbrella of a new regional authority: the Greater Vancouver Regional District (GVRD). In 1969, the GVRD further integrated its approach by appointing its first regional director of planning, Harry Lash.

Having averted the doom of a yet further expanded freeway network, Vancouver’s new political ideology spelled ‘liveability’ and was embraced equally by the municipal and provincial governments. It is not unequivocally clear where precisely the term originated or who first used it. In his book Planning in a Human Way, from 1976, Harry Lash attributes the first use of ‘liveability’ as a planning term to Alan Kelly, the regional board’s chairman from 1972 to 1975. Kelly allegedly launched the word at a weekend seminar of the GVRD Planning Committee in 1970 as the new goal for Greater Vancouver: ‘The Livable Region Plan would be a map showing where housing, commerce and industry would go; where the roads, transit links and parks should be located; and it should show where those things should be built.’ In that meeting, Kelly said that ‘the expert’s job was to produce the map, maybe with some explanation; then, since no one in his right mind would expect everyone to agree that what the planner had produced was good, the planner had better produce the map in jig time so that the arguments could start and the board decide who was right’.

Despite the bravura with which it was launched and the unquestionable status it was beginning to acquire, nobody at the time seemed to know precisely what liveability entailed, let alone how to implement it in the form of planning policies.

[….]

In the end, the conclusion was predictable. ‘Quite suddenly, early in 1972, we did discover the signpost: find out from the public what livability means; abandon the idea that planners must know the goals first and define the problem; ask the people what they see as the issues, problems and opportunities of the region. We decided to go to the public and simply raise the question of livability, with as little “inspiration” from ourselves as possible and see how they responded.’

In short: liveability is what the people say that liveability is. Following that conclusion, Lash led an extensive public consultation process which would last until the end of his tenure in 1975. The findings of this process are laid down in the report which would serve as his main legacy: The Livable Region 1976/1986: Proposals to Manage the Growth of Greater Vancouver. The report made five recommendations on how to achieve a liveable region: residential growth targets in each part of the region; a balance of jobs to population; regional town centres; a transit-oriented transportation system; and regional open space. It painted an optimistic picture of the cumulative result of these measures in its description of the region in ten years: ‘Greater Vancouver is an enjoyable place to live. No other Canadian metropolitan region is so close to mountains and water, farmlands and forests, yet so cosmopolitan in its variety of culture, educational opportunities, and business activities … During the past decade we have seen great changes in this beautiful area. There has been a burst of new restaurants, shops, and theatre and music groups. The Vancouver Region is a livelier place than it was ten years ago.’ It also nonetheless included a note of caution: ‘However, the region’s fortunes may not last for much longer’.

The report’s horizon qualifies as uncanny foresight. In 1986, to celebrate its centenary, Vancouver hosted the World Expo on Transportation and Communication. What should have been (or perhaps was) a defining moment in the recognition of Vancouver as a global city also revealed the first cracks in the city’s policies of considered urban growth and carefully guarded social diversity. In the run-up to Expo ’86, pressures on the housing market resulted in the eviction of 500 to 850 residents from the Downtown Eastside and surrounding areas. That same year, the old Non-Partisan Association regained control of the city council for the first time since 1972.

Living first

The next ten years marked a period of strong growth for Vancouver, both economically and demographically. From a population of just under 1.5 million in 1986, the GVRD crossed the 2 million mark shortly before the turn of the millennium. An important driver of the district’s accelerated growth was immigration from overseas—particularly from Hong Kong, uncertain about its future after its reversion to China. Like Hong Kong, Canada was part of the former British Empire and Canada’s relaxed immigration policies, coupled with a large existing Chinese community in the city, made Vancouver an obvious choice for relocation.

Anxieties about the consequences of such growth manifested as early as September 1990, in Steps to a More Livable Region, the sequel to The Livable Region 1976/1986 and the preparatory report for The Livable Region Strategic Plan from 1996. The report describes Vancouver’s liveability as a composite of its natural setting, its unique and envied lifestyle, and a thriving economic and cultural life—all under a perceived threat of an imminent ‘degradation which plagues so many large cities in the world’.

No longer was liveability something that needed to be dis- covered, it was something that needed to be protected from unfettered population growth. The answer was sought in the development of ‘a compact metropolitan region’, one that preserved the area’s natural setting and farmlands at all costs.

The scarcity of land that inevitably followed, coupled to a steady decrease in the number of persons per household, created considerable pressure on the housing market. Despite the enhanced regional cooperation, most of these pressures landed on the city of Vancouver itself, which, through its ‘living first’ policy, had opened the gates for extensive residential developments in its downtown area and waterfront land following the dismantling of the Expo ’86 fairgrounds.

Under the subsequent pressure of the 1990s property boom in Vancouver, it became common practice among developers to go after plots they suspected the city might be open to allow- ing a higher quantum of residential development than strictly prescribed by the zoning plan. This so-called ‘rezoning’ of plots proved highly profitable—both for developers and for the city itself, the latter claiming its fair share of the upturn in land values (sometimes taking as much as 75 per cent). Moreover, the city could insist that new developments created certain ‘planning gains’ in the form of public facilities like libraries or museums or that developers contribute to the financing of public spaces and public parks.

Although arguably a conflict of interest, the ‘joint property venture’ between the public and private sectors benefited both sides. In the 1990s, Vancouver’s downtown successfully absorbed a population increase from 40,000 to 80,000—all of which occurred in the context of a total city population, which, even after the increase, didn’t equal more than 600,000. In fact, the approach worked so well that a new set of problems was created in its wake. The ‘planning gains’ did not cover the provision of affordable housing or commercial uses. As a result, Vancouver’s city centre came to suffer a desperate lack of both, with many of its wealthy residents having to commute to the suburbs for work while the downtown area increasingly needed to be serviced by less wealthy residents travelling in from their affordable homes in the suburbs. Twenty years after its introduction, Vancouver’s ‘living first’ policy had turned it into a strange, inverse echo of the scenario it had so desperately tried to avert in the 1970s and against which the whole idea of liveability had been predicated.

Liveable, sustainable, affordable

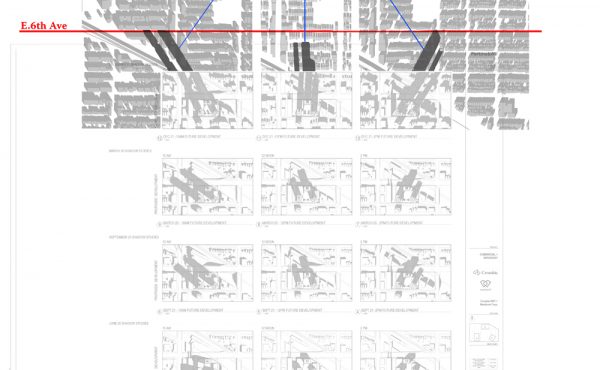

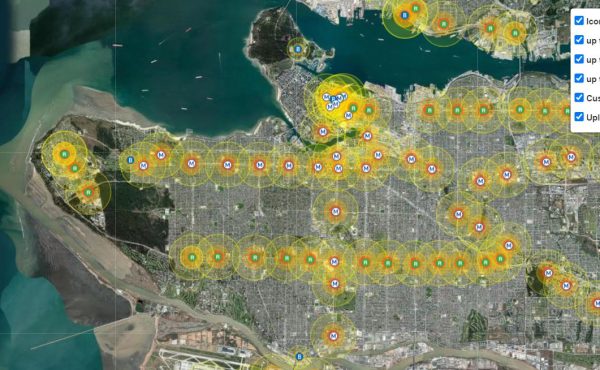

In 2005, a moratorium was announced against further high-end residential development in Vancouver’s downtown. To spread development more evenly across the city, then-mayor Sam Sullivan launched the concept of ‘EcoDensity’, in which future residential growth was to be accommodated via a series of dense urban developments around transport nodes across the city.

According to the EcoDensity Initiative Document, the approach would ‘reduce housing costs, increase housing choice, reduce urban sprawl, alleviate traffic congestion and reduce fossil fuel emissions, preserve industrial and agricultural land as well as green space, make transit and community amenities more viable, keep taxes low and the local economy vibrant and healthy, reduce Vancouver’s ecological footprint and keep Vancouver’s high rank in the quality-of-life surveys’. EcoDensity was to make Vancouver ‘more livable, sustainable and affordable’ and ostentatiously ticked all the boxes required for doing so. To its critics, however, it was more of the same: a mere veil to yet more luxury high-rises encroaching on the city. Many of the proposed high-rise clusters replaced existing single-family homes, with many local communities complaining they had not been properly consulted. Once again, planning had become a top-down affair, dictated by infrastructure and the demolition of existing neighbourhoods. Forty years after the Great Freeway Debate, Vancouver was back to square one. Jane Jacobs died in 2006, the same year the initiative was launched.

Top of the list

That year, for the fourth time, Vancouver earned the top position on The Economist’s Global Liveability Index. It would retain that position for another five years, until 2010. However, in the 2000s the notion of what constitutes liveability had come to differ significantly from the early seventies. No longer was the term associated with the counterculture that had flourished in the context of protecting local communities. Liveability had become mainstream.

And with that came a distinct twist on the post-materialist values that had once underlaid the term. Inevitably, these values were rediscovered as a source of material value, ready to be marketed and consumed. Liveability inevitably comes at a price. In the time that Vancouver held the top spot on the EIU liveability index house prices in the city increased by more than 300 per cent, more than they had in all the previous century. The cost of living proved directly proportional to the city’s increased liveability.

The fact that the term ‘liveability’ had never been defined properly in its own right—initially it was oppositional to prevailing powers, but once these had been overturned, it was left for ‘the people’ to define—made it a welcome hobby horse for almost any political course. (After the NPA reclaimed power in 1986, use of the word only intensified, despite the massive increase in house prices.) In retrospect, the meaning of the term evolved neatly in line with the political leanings of Vancouver itself—at first activist, then participatory and finally consumerist. Liveability was whatever Vancouver said it was. The term and the city had become synonyms, making any further search for meaning redundant. When it comes to Vancouver occupying the number one spot on The Economist’s list, one wonders: was Vancouver a reflection of the properties on the list, or was the list a reflection of the properties of Vancouver?

All three former directors of Vancouver’s planning department—Ray Spaxman, Ann McAfee and Larry Beasley—enjoy active retirements in the private sector, selling ‘Vancouverism’ to municipalities globally as a formula to emulate. With their city consistently occupying a high position on liveability rankings, the facts speak loudly. What the Guggenheim was to Bilbao, The Economist’s Global Liveability Index is to Vancouver: the validation for a city, seemingly emerging out of nowhere, to suddenly qualify as a global model. The home of a world-class museum … the world’s most liveable city—captured in objectively verifiable data, be it visitor numbers or expatriate feedback, the success is beyond question.

Conclusion

Given the astounding popularity of liveability rankings over the last two decades, no longer do Mercer, The Economist or Monocle hold a monopoly over the idea. Their number now runs into the dozens: the EU Urban Audit, the OECD Better Life Index, the Livability Index by the American Association of Retired Persons, the Property Council of Australia’s Australian City Liveability Index, the Healthy Livable Communities Urban Liveability Checklist, and so on.

[….]

The more such rankings proliferate, the more their core purpose—to relate the idea of liveability to measurable properties—becomes questionable. Their sheer number invalidates their aura of objectivity. Pending the criteria invoked, any city can top any list at any time. Increasingly, the lists feel like the self-portraits of cities looking to make their mark. Take the properties of a (any) city, package those as key factors for liveability and the same city emerges as the fair winner.

Once again, the idea of liveability becomes elusive. The dismissal of material, and therefore measurable, facts of life in the 1970s led society to project the idea of measurement on immaterial values in the decades after, only to find out that the value of these was, indeed, immeasurable.

[….]

It seems that the more things we can measure, the fewer we can change.

Postscript

In 2017, the City of Vancouver introduced the Empty Homes Tax on properties that stand vacant more than six months. Ever since the city ranked top of the Liveability Index, property speculation and condo ownership by absentee landlords have become major problems. In 2018 the Downtown and West End districts reached record-high vacancy rates—5 and 6 per cent, respectively—safeguarded for residential uses as part of the city’s mid-eighties ‘living first’ policies. The net revenues of this tax are to be invested in the construction of affordable homes. The spirit of Jane Jacobs is still out there, if only because of her seventy-year-old son Ned, who acts as a tour guide through what is left of Mount Pleasant—once a bustling working-class neighbourhood, it is presently one of Vancouver’s most sought- after places for real estate investment and unaffordable for anybody on a median salary. Twenty years into the new millennium, living and liveability are two very different things.

***

For more information on Architect, Verb.: The New Language of Building, visit the Verso website.

**

Reinier de Graaf (1964, Schiedam) is a Dutch architect and writer. He is a partner in the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), where he leads projects in Europe, Russia and the Middle East. Reinier is the co-founder of OMA’s think-tank AMO and Sir Arthur Marshall Visiting Professor of Urban Design at the University of Cambridge. He is the author of Four Walls and a Roof: The Complex Nature of a Simple Profession and the novel The Masterplan. He lives in Amsterdam.

One comment

The vacancy rate for “West End/Stanley Park” and Downtown were 0.6% and 1.1% respectively in 2018 according to CMHC data. Not surprising given that he cannot even get basic facts like this right that his entire history of Vancouver was totally wrong as well.