By John Lorinc and Alex Steep

At its final meeting of the fractious 2010-2014 term, City Council gave its blessing to what will become one of the few new parks to be built in recent years in the high-density corridors of the downtown. After years of fraught and often frustrating negotiations, Toronto Centre councillor Kristyn Wong-Tam persuaded Lanterra, the developers of a large provincially-own piece of land on the south side of Wellesley, to hive off a 0.6 hectare portion of the property for a park, to be located at 11 Wellesley. The city also managed to buy more land on the site by using Section 42 funds provided by a pair of developers working on buildings nearby (the sums have not be disclosed).

“Rarely do you have the opportunity to work on a piece of land that’s so significant, in such a significant location, with the added advantage of having it become part of the public realm,” Mark Mandelbaum, chairman of Lanterra Developments, told The Toronto Star.

That deal, however, is the exception. When David Mirvish submitted a development application to knock down the Princess of Wales theatre and two King Street warehouses to create a gallery/condo tower complex designed by starchitect Frank Gehry, city officials asked if he’d set aside some of the property, which occupies much of a city block, to create a parkette.

Mirvish refused, offering instead to contribute a cash-in-lieu payment, to be deposited in the city’s parkland acquisition reserve fund. (See Sidebar: How the parkland levy system works)

That kind of offer has become a common trade-off. Ever since the city changed the rules governing parkland dedications, builders have been opting – often with the blessing of the local city councillor – to provide dollars instead of land.

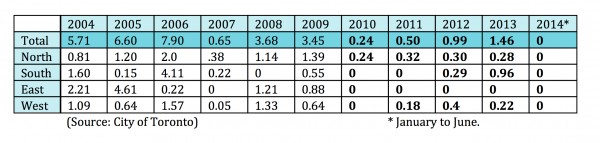

According to documents obtained by Spacing through an access to information request, the city, between 2004 and 2009, received on average 4.9 ha of land per year through dedications by developers. In other words, builders aiming to erect residential projects on a parcel of land would transfer title of a portion of those properties to the city’s department of parks, forestry and recreation, to build a park.

Between 2010 and 2014, the documents reveal, that average annual tally plunged to .64 ha – the size of a regulation soccer pitch – for the entire city.

Annual dedications of parkland, by district, in hectares

Not coincidentally, the funds flowing into the parkland reserves, but especially via the new “alternate parkland dedication” formula which came into effect in early 2008, have jumped sharply, from $9.9 million in 2010 to $36 million in 2013, according to a two-year-old staff report. Indeed, between 2010 and 2013 the city collected $94.2 million through this new formula – a figure that accounts for almost half the parkland levies collected by the city during that period.

While cash may seem like an attractive alternative, especially for a cash-strapped municipality carrying lots of debt, the practice of accepting money instead of land has become highly problematic from a planning policy perspective.

Here’s why.

When a builder hives off land on a development parcel to create a park, the additional open space will be physically close to the additional population generated by the new residential units. But when the city accepts cash, there’s no guarantee the money will create or improve open space in the proximity of the project.

Under the city’s 14-year-old policy framework, revenue from Section 42 park levies can be spent on city-wide green spaces or within the administrative district where the development has occurred. So cash from a downtown high rise could flow into a new park or park improvement project in North Toronto, or High Park.

The amounts are not trivial: In the case of wards 20, 27 and 28, which together generated $142.6 million in levies between 2011 and 2014, the policy allows a quarter of those funds to be spent anywhere in Toronto, and another quarter to be allocated to parks anywhere within South District.

With the alternate deduction rate, the city’s policy is that the funds be spent on parks projects that are “in the vicinity of” or “accessible to” the development from which they originate. But there’s no definition of what those terms mean. Nor does Parks, Forestry and Recreation (PFR) provide any targets or benchmarks for how and where those parkland revenues flow, especially the portions to be spent on park improvements. Last, it is difficult to discern, based on the city’s reporting, whether those dollars has found their way to areas deemed in the official plan to be deficient in public open space.

Besides the lack of transparency, the policy is undermined by the fact that a single set of rules must apply to two radically different property markets.

Councillors, in theory, can influence whether developers offer cash or land, and some argue that the city should turn down the money. “The councillors have to say ‘no,’” asserts Scarborough Southwest councillor Michelle Berardinetti, current chair of the parks and environment committee.

It’s an easy position to take in a low-development ward. In suburban areas where land is plentiful and inexpensive, councillors have leverage over builders and can compel them to ante up land for a new park.

The dynamic downtown is radically different. Toronto Centre councillor Kristyn Wong-Tam says she tells high-rise builders that the city wants land, not cash. But developers putting up a condo on a small parcel mostly balk, she adds. “[They say], ‘Oh councillor, that’s not doable. It’s easier if the city acquires the land.’”

There are other impediments to acquisitions in high growth zones: For one thing, the city is legally prevented from buying property at prices above the assessed value, even though market real estate prices today tend to be far higher. PFR officials, in turn, don’t like small parks or squares, which are typically what’s on offer with most downtown developers who are prepared to provide land. “Parks staff aren’t interested in small parcels,” says Wong-Tam.

The bottom line is that developers will give cash in areas that desperately need open space and real estate in areas that aren’t experiencing population growth or speculative pressure. But when it comes to buying land, the city, despite its large reserves, simply can’t compete in areas facing sky-rocketing real estate values.

“It’s a really serious problem,” observes Willowdale councillor John Filion, whose ward includes both high-density towers and low-rise single-family homes. “The city takes a very short-sighted approach and will certainly pay the price in the years to come.” In his view, council should establish special parks reserve funds specifically for high-growth nodes and ensure that 100% of the park levy revenue is spent in those areas. “The money should stay in the area where it’s generated.”

Part 1: All built up but no place to grow

Part 2: Where the money flows

Part 3: The perils of cash-in-lieu

Part 3 sidebar: Section 42 explained

Part 4: The tale of two parks

Part 5: The system worked (slowly) for a west end park

Part 6: Are privately-owned public spaces the answer to parks deficit?

8 comments

Nice to see some investigative journalism in Spacing. I pretty much love everything Spacing does already, but this is a nice addition.

This series of articles could do a better job at providing what area’s are actually in need of new parks. And what the criteria for ‘need’ actually is.

City’s are meant to get dense and grow around their existing parks. Parkland isn’t something that’s meant to grow and grow and grow as you urbanize.

11 Wellesley is one great example of this bizarre planning policy. From the tone of the article you would think the area has no other parkland nearby. But in reality, Queen’s Park is a two minute walk away. There was no need for a new park in this area.

Trish, on day one, there’s a map — which is part of the City’s official plan, and is theoretically used to guide investment — that ranks Toronto neighbourhoods by parkland per 1000 residents. If you look at the map, which was published in 2002, the core areas are all deemed to be short on public open space according to a parkland provision metric that the city uses for planning purposes. Since then, as the series has shown — and as a few minutes of strolling around downtown looking up with confirm — the intensification in these same areas has increased dramatically. According to data provided to me by the city, there were 26,117 new residential units approved between 2011 and 2014 in Wards 20 and 27 alone, which translates into roughly twice as many new residents. That figure, incidentally, represents 31% — almost a third — of all new units approved across the entire City of Toronto (83,677) between 2011 and 2014. So if you combine these data, and then add up the new public open spaces created in areas facing high density intensification, it is difficult to know how anyone could reasonably conclude that the city is keeping up. Yes, we can build on every available square-foot of space. That is an option. But I wouldn’t want to be living in that kind of city two or three generations hence.

I think the statistics suggest the city’s required amount of parkland per person might be too high. I’m not against parkland, though I think we should build it rationally.

A better way to do this might be to compare the amount of parkland Toronto has to other large cities. How do the stats actually compare? What’s a rational amount of parkland? Is the city out to lunch as to how much it thinks we actually need?

And yes the core has intensified greatly in the last few years, though many of our parks were built to withstand these larger loads. And many of our parks are still underused even with all the huge increases in population.

Lastly, as the population increases the amount of parkland the city requires per person will need to decrease. We’ve only a set amount of land. The population is supposed to double in the next 15 years and there is no rational way to more than double the parkland available downtown.

John, great article, but I gotta disagree with the the figures in the Official Plan that you use to form your argument. You can use the figure as a baseline but it needs to be looked at with a little flexibility. Thousands of people have move to the downtown core in the last few years for a variety of reasons and I highly doubt that the provision of park space was one of them. People in different areas use or have a need for parks for different reasons and its false to think that one size fits all. In this case its that every area requires a predetermined amount of park space per resident. If someone really values park space they can move to a neighbourhood where there is great access to parks, if they like subways they can move close to transit lines and if they like to commute they can move close to a highway etc. etc. If we just start doing things to fit into formulas then we risk getting into a situation where we plan and build things that we may not need but only build it because someone else or somewhere else has it. Downtown could use a bit more park space, but at the cost of land it would benefit more if we improved existing parks.

One last thing, as a planner I suggest that you don’t put so much trust into planning documents and the metrics they use. You should not assume that something in the Official Plan is the right thing to do.

As someone who works with the city as part of their job, I can say a large number of parks projects were put on hold as soon as the Ford’s took office. I think in the next few years more of these projects will reveal themselves and the picture won’t seem nearly as bleak. The city does understand we need more public space and it also knows it has to be creative in order to make it happen. Does anyone recall the stacked 4-pad ice rink arena? We’ll need projects exactly like that in order to actually fulfill the parks requirements. As our city grows upwards, our parks will need to as well.

Though, all-in-all we should be thinking positively about this. The city has a vast amount of money saved to spend on parks right now, which is actually an amazing thing. We should be thinking of creative ways to use that money, rather than looking it at in such a negative light. And if your really feeling down, go to regent park and visit the aquatics centre to see what the city can be when it has some cash on hand.

Thirdly, lets all imagine this stock pile of money is to pay for a giant park over the rail lands! Or maybe we’ll get our own version of the highline on the gardiner! The possibilities are endless! I’d much rather we have one mega project, than one thousand tiny condo parkettes. Toronto’s own central park.

Also! Maybe it’s all to pay for the hearn sports complex proposed a few years back?! Who’s with me!

I’ll have to disagree with the idea that the parkland funds should be linked directly to the development area they were contributed from. We need to start thinking about the betterment of the entire city, and not exclusively the core. Downtown is benefitting from parks funds both provincially and nationally with the development of the Waterfront, Fort York, Ontario Place, and Corktown Common.

What if instead of building tiny parks near condos, we used the funds to build another Trinity Bellwoods at Jane and Finch. I think the money would go far further up there, and it would help spur development that might not otherwise occur. If other parts of the city began taking more density, then the core would be under less pressure to provide more parkland. It’d be a win-win-win situation. And it’s only in the more suburban areas of our city where large parkland developments are actually possible.