On a warm spring afternoon, the park on the corner of Sorauren and Wabash avenues in the west Toronto neighbourhood of Parkdale looks like a perfect dream of urban open space: a city block of green bordered by tree-lined streets, families with strollers, kids playing lacrosse, and neighbours mingling at the farmer’s market whose winter home is in an early 20th-century brick office building that’s now a renovated fieldhouse. There’s even a guy on stilts making balloon animals.

By all appearances, this park — the go-to spot for thousands of residents in a fast-growing neighbourhood — looks like a triumph of good planning and community engagement. The park even gets a lot of the credit for new investment pouring into a formerly industrial corner of Parkdale.

Sorauren Park — bounded by Sorauren Avenue, Wabash Avenue and the railway tracks that will soon carry passengers to Pearson Airport — is, in fact, all those things.

Its most recent expansion, the creation of what’s called the Sorauren Park Town Square, is one a handful of recent parks projects — all of them partnerships between the city, local residents and philanthropic funders — that are heralded as the shining examples of the city’s parks policy and resource allocation. “How is it that civilization stays together?” Ward 14 city councillor Gord Perks asked at the Town Square opening last summer. “The answer is right here behind you.”

But it’s also an astonishing example of the hurdles and hoops the city throws up as obstacles for even the most deserving and forward-looking parks projects and their hard-working supporters.

The neighbourhood has these facilities because open space activists have spent two decades jumping — as well as bowing, scraping, baking, schmoozing and strategizing — to assemble the crazy-quilt of funding required to create high-functioning open space.

They even managed to pry loose a small amount of Section 42 money, which makes them the only small park partnership project in recent years to tap into vast parkland reserve fund that the city has been sitting on, like some municipal Smaug hoarding dwarf gold.

Even so, the city is still asking local activists to sweat for every park amenity, right down to the benches and the bicycle rings they are currently in the process of adding to the new square.

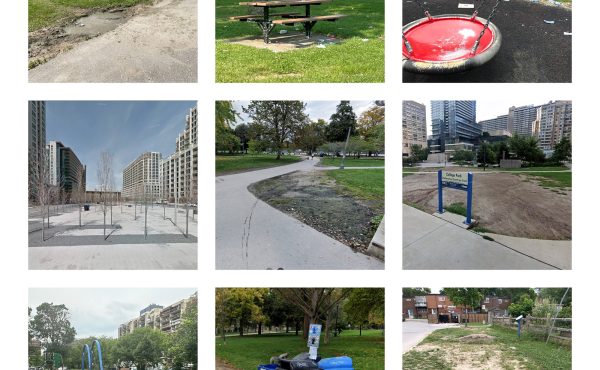

When Spacing set out to find Toronto park development success stories that were exceptions to the city’s reluctance to allocate funds to parks projects, we were repeatedly pointed toward such partnerships.

Yet many of these projects are modest playground expansions in suburban areas far from the downtown wards that generated tens of millions in park levies. They include the $350,000-plus rebuilding of the Jamie Bell Adventure Playground in High Park; $200,000 spent to buy and plant black cedars to restore the Hedge Maze on Centre Island; and a $250,000 multi-use rejuvenation of the Rotary Peace Park on Lake Ontario in New Toronto.

But the $405,000 Sorauren Park Town Square is the only partnership that drew on the Section 42 funding. Of that total, only slightly more than 10%–$48,000–came out of the parkland reserves.

The neighbourhood, led first by long-time residents and community parks activists, has waged a fierce and lengthy battle for every square metre of green space and recreational improvements in a space that served, until the early 1990s, as a TTC bus repair yard, and was destined to become a new mega-facility for public works.

Residents fought that plan until the city capitulated. It spent $1.2 million to clean up the industrial contamination on the property. Parks contractors covered the 2.4 ha brownfield site with soil, planted trees, and built a baseball diamond and tennis courts.

Then, almost as soon as the park opened in 1995, neighbourhood residents launched a campaign to persuade the city to renovate the linseed oil complex into a recreational centre for the under-served community, which had begun attracting new residents and millions of dollars in loft conversion investment.

The city bought the old Canada Linseed Oil Mills buildings for $2-million in 2000. But, pleading poverty, the city maintained it could not afford the $20 million-plus investment in the recreation centre, and even sought proposals for a public-private partnership that would see condos built on the site to help finance recreational facilities.

The sole P3 proposal proved unfeasible. But it showed the Sorauren activists they could not risk waiting for the city–or risk seeing the linseed property sold to a developer. They set up an incorporated entity to carry the plan forward, establishing the Wabash Building Society (WBS) to raise money for park improvements themselves.

WBS decided to start small. The group proposed a $400,000 renovation of the derelict linseed oil administrative office – a charming brick building with deco-style features that once operated as an after-hours speakeasy – into a fieldhouse. After it opened in 2008, the City of Toronto and the Wabash Building Society were awarded Canadian Urban Institute’s Brownie Award for successfully converting a “brownfield” site for community use.

The City directed Section 37 funds from nearby loft development projects to improve the fieldhouse, now in constant use by community groups. This project provided the Wabash Building Society with a track record when it came time to tackle the next stage of their park reno plan.

It also taught them the value of taking what long-time members call “baby steps.” In 2009, the WBS set out to raise the $405,000 needed to transform land that had once held the linseed company’s grain elevator into a 21×27-metre square that can be used for local events, such as dances and outdoor films, as well as the farmer’s market.

When this new “town square” was officially opened last summer, its funding story could be seen clearly on the banner thanking donors: somewhere close 200 names, the culmination of five years of bake sales and funds donated in memory of loved ones who had themselves loved the park.

The largest sum, $155,000, came from City of Toronto capital funding. Other contributions included $125,000 from a Live Green grant; $61,000 from the Wabash Building Society’s Reserve Fund; $16,000 from community fundraising and the Toronto Parks and Trees Foundation; and $48,000 from the Section 42 parkland fund.

How did the Wabash Building Society manage to score that cash?

Sorauren Park activists praise their elected representatives, especially Ward 14 councillor Perks, for paving a pragmatic and principled way to City Hall. “He’s been a brick,” said neighbourhood realtor Chander Chaddah, who has been on the Wabash Building Society board since its inception. Perks, in turn, credits former Ward 27 councillor Kyle Rae for teaching him how to successfully negotiate access to municipal funding on behalf of constituents.

Strategic civic panhandling

“Win win win” has been the WBS mantra for what’s now going on a decade. (“It’s been a bit of a process,” Chaddah said, “but an enjoyable and happy process.”) Yet the strategic panhandling continues. Sorauren Park Town Square has been the recipient of $10,000 from the TD Bank’s Friends of the Environment foundation, money used to purchase and plant 48 new trees and shrubs, which will be cared for by community volunteers over the next two years.

According to Rob Richardson, manager of Toronto’s PFR Partnership Development office, Sorauren Park activists recently raised an additional $11,400 for six new benches for the town square. In addition, Metrolinx — which will soon operate UP Express along the park’s eastern boundary — provided $1,000 for 12 bike rings. The next community fundraising phase is aimed at building a trellis on one side of the square as well as an open-air community bake oven.

The strategy during the Ford administration was to keep public investment in community parks development under the radar. “We snuck this into the budget so that the person elected four years ago never found out,” Perks said at the July, 2014, Town Square opening. The plan, parks supporters confided, has been to keep funding tiny projects that inch across the park until they are back to where this group started a decade ago: at the factory building the WBS has always hoped would some day become a community centre.

As of last week, it looks like the Sorauren Park activists will get what they want. The process that Perks calls “incrementally recapturing and building on this space over a generation” has paid off. City council has allocated $34-million toward the design and construction of the Wabash Community Centre in its 2014 to 2023 capital budget. The project is now seventh on a list of eight approved community centres for under-served Toronto neighbourhoods.

The community is cautiously optimistic. “While the news is encouraging,” the WBS wrote on buildwabashnow.org blog, “the community centre has been a line item in the City’s budget since at least 2000.”

The moral of the Sorauren Park story is that even the most effective communities must recognize that creating a new full-service public park is something to be done for the next generation. WBS activists praise themselves for their fortitude, but they also point out that the children that were in utero during the inaugural meetings are now old enough to attend meetings as young adults. “All the stars have to align,” one of the WBS founders said. “Sometimes it takes a long time for that to happen.”

Perks, for his part, said the city needs to adopt a completely new mindset about open space. “It’s a public infrastructure issue. People have start thinking of parks the way they think of sidewalks.”

Part 1: All built up but no place to grow

Part 2: Where the money flows

Part 3: The perils of cash-in-lieu

Part 3 sidebar: Section 42 explained

Part 4: The tale of two parks

Part 5: The system worked (slowly) for a west end park

Part 6: Are privately-owned public spaces the answer to parks deficit?

2 comments

Continuing our cities parks crisis, it was announced today that Moss Park will be having a complete makeover and the 519 will be building the first LGBTQ rec centre on the site. This will likely take a few years to complete at some cost to the city after years of the LGBTQ community pursuing this goal. The public generally feels awful about this outcome as it did not occur in a short time frame, and required hard work. A man related to the project expressed his dismay at the parks crisis, expressing his dismay that he couldn’t have the park in 20 minutes or less.

soarauren park is a great success story in a community fighting for park space. I remember trying to break in to the ttc yard to explore when i was a kid. The thing that baffles my mind is that it has taken so much effort to raise money to improve this park yet recently the city spent over 2 million$ to buy an old plaxa qt queen st. And callender ave to build of all things a new parking lot. And even more recently paid a few million dollars for a tiny new park at king and dufferin. I grew up in parkdale and have never heard of anyone asking the city to spend millions to buy a tiny new park While down the road at sorauren the residents are fighting for every dollar they can get. And how about those 2000$ benches. Please. They could have been built by talented locals for a fraction of the cost. Regardless of all the bureacratic hurdles the community has rallied to create a great park that is unrecognizeable from the scrap yard i remember as a kid